Kweli’s First Annual Children’s Book Writers Conference

Wednesday, January 21, 2015

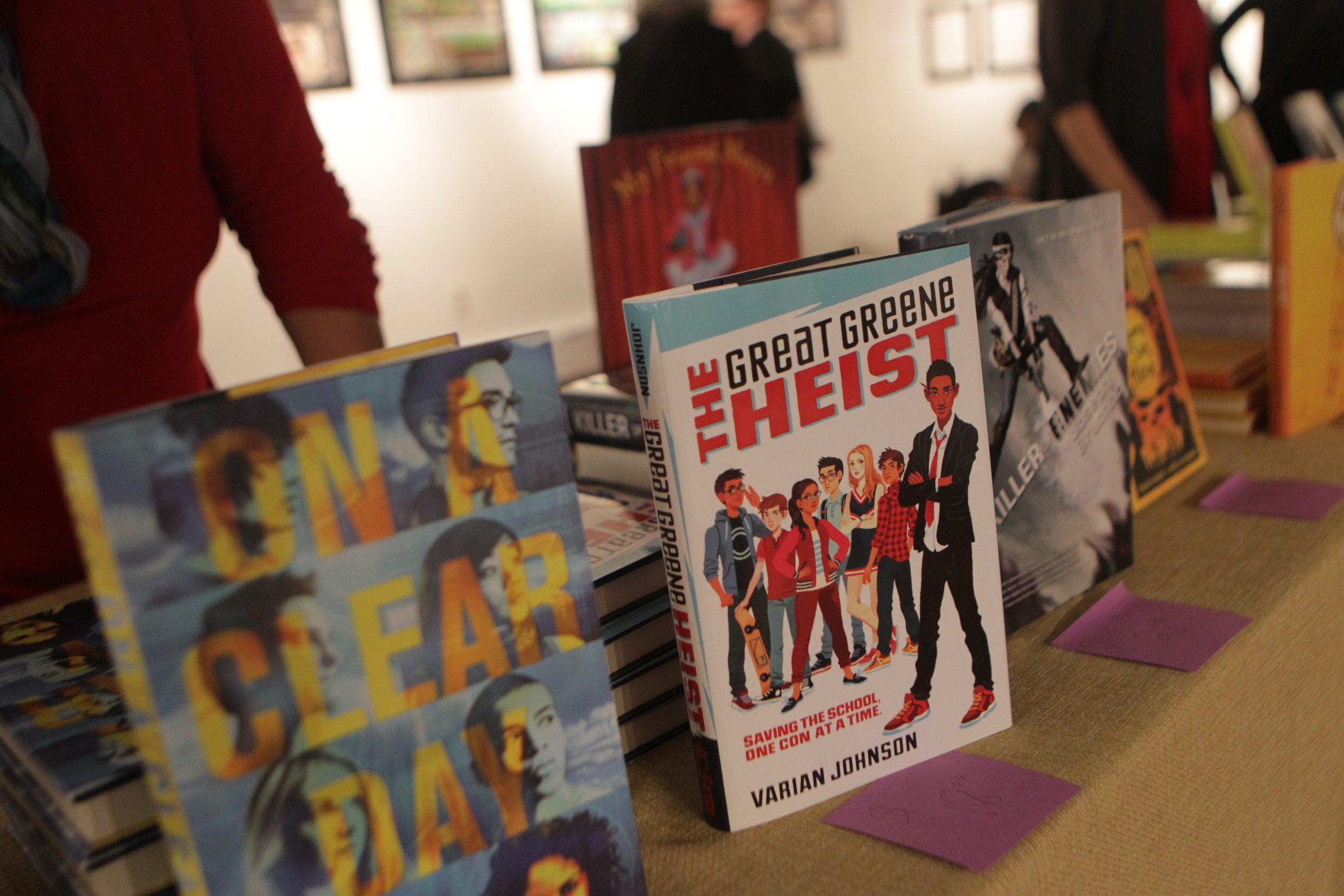

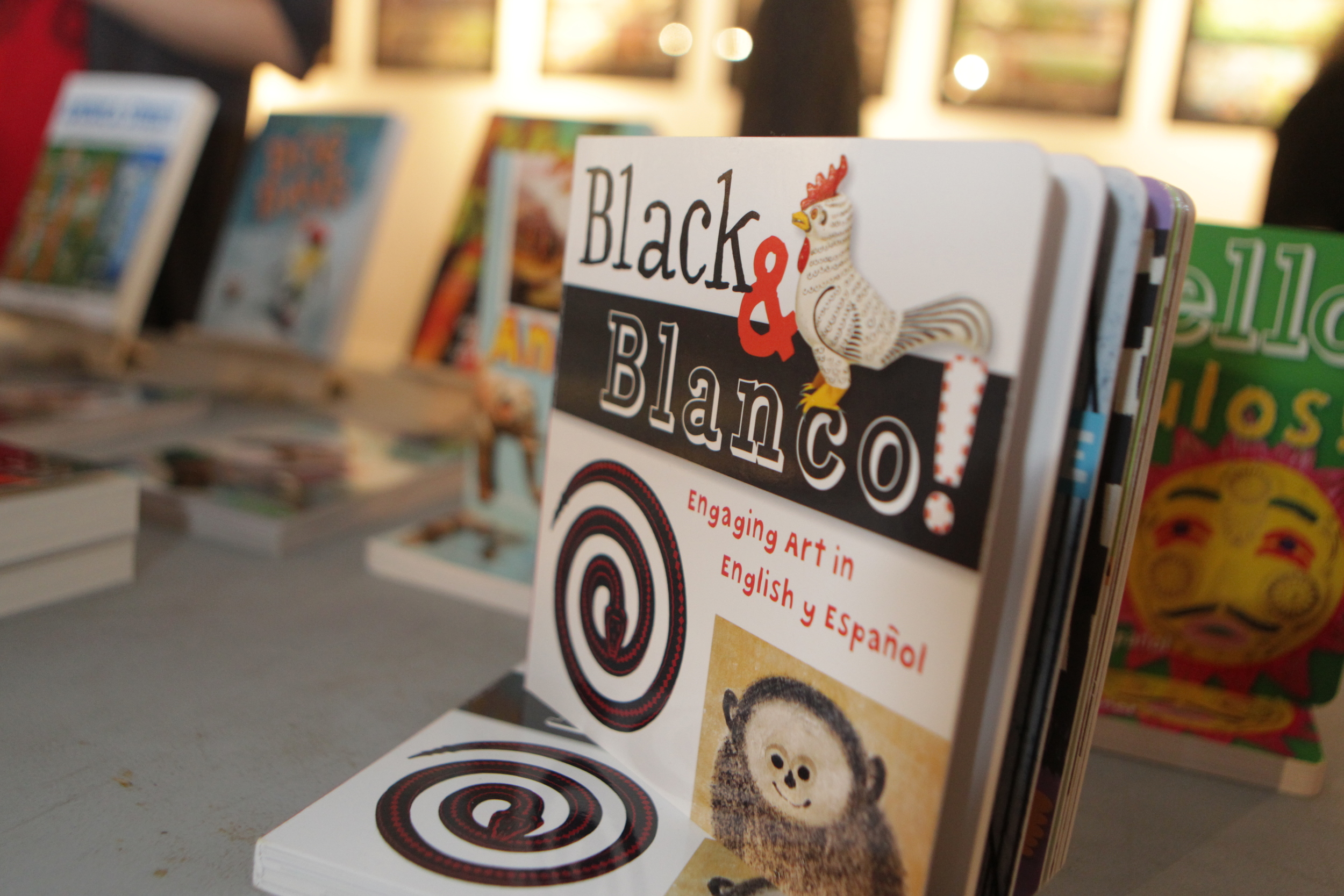

Poet’s Den Theater & Gallery

East Harlem, New York

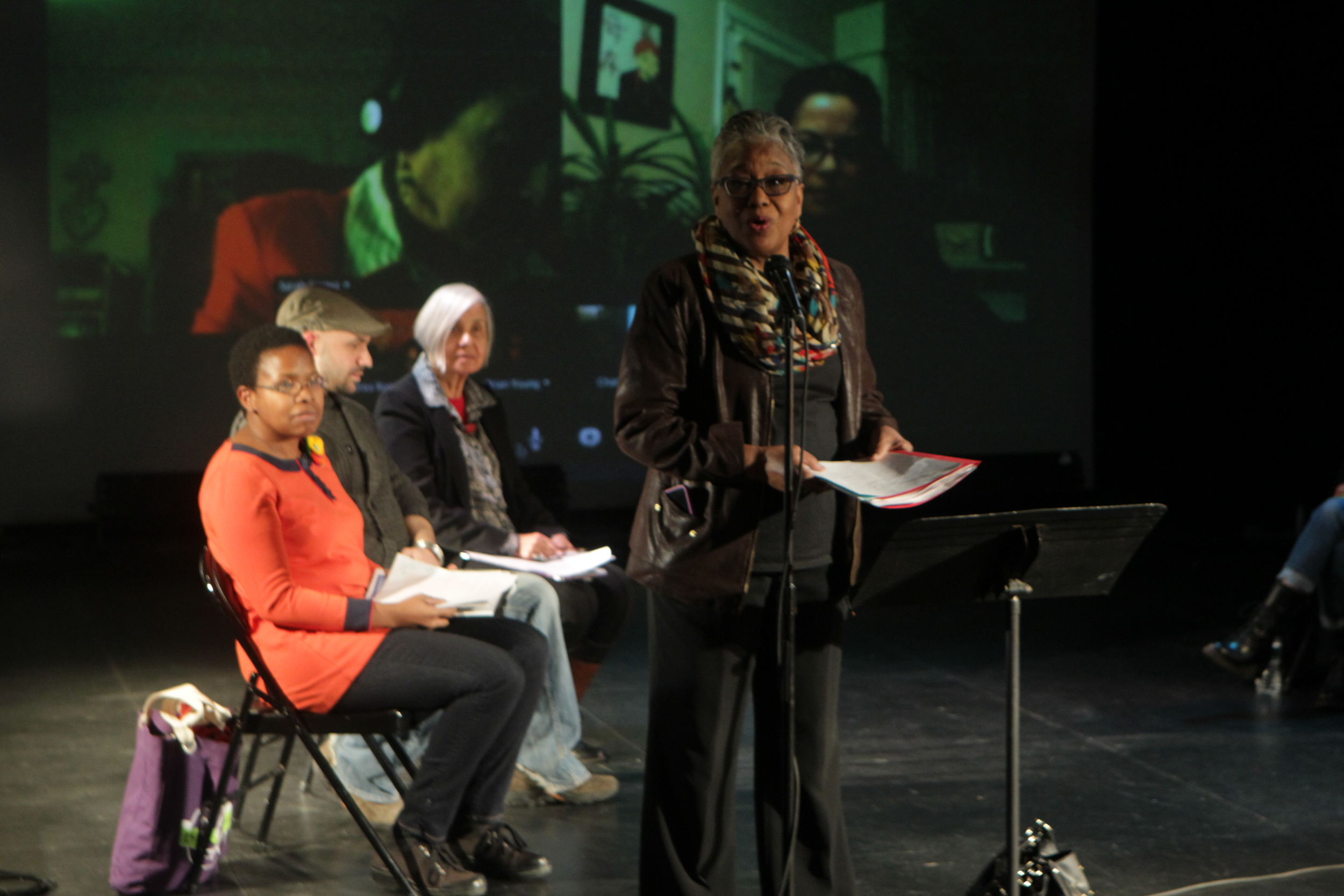

CHERYL WILLIS HUDSON: Thank you all for joining us this evening at Poet’s Den Theater as we honor the legacy of Walter Dean Myers and celebrate young people’s literature. Walter reached out to young people and he reached out to Wade and myself when we first started our publishing company. Really, the first time we appeared together was at a book signing at Toys R Us in 1990. So I am very honored to welcome you here and I think that it is going to be an engaging and insightful evening. A lot of you may have been inspired by the works of Walter Dean Myers, whether you realize it or not. In a career spanning over 45 years, Walter wrote more than 100 books for children of all ages. A few of the authors he inspired will soon take the mic. They will be reading to you tonight from their new work. Then they will participate in a panel discussion on diversity in storytelling. Tracey Baptiste, Daniel Jose Older, Danette Vigilante and Leila Gomez Woolley are waiting backstage. And Dr. Charles Johnson and his daughter Elisheba Johnson are joining us via Skype from Seattle. Dr. Johnson edited a special issue of the American Book Review magazine: The Color of Children’s Literature. You all received a complimentary copy of the magazine tonight. I want you to enjoy the program, and to participate and to interact with one another. That is what Walter would have encouraged. As many of the editors here know, Walter was a giant of a man, but he really was very down to earth. I think that this conference will be a wonderful way to honor him. So as they say in the black church, "welcome, welcome, welcome."

PANEL 1

OLUGBEMISOLA RHUDAY-PERKOVICH: Dr. Charles Johnson, in the introduction to The Color of Children’s Literature, you wrote that “the genre of children’s literature must change now as we experience the browning of America.”

I’m going to go over a couple of stats that I think a lot of us already know. It is estimated that by 2019, approximately 49% of U.S. students enrolled in public schools will be Latino, Black, Asian or Pacific Islander or American Indian. Another stat: In a survey of children’s books published in 2013 by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin, the researchers found that out of 3200 traditionally published children’s books, only 223 were by authors of color and 253 were about authors of color. These statistics refer to those we call people of color and they are including those who are Native Americans or American Indians. They are also including books by and about LGBT people, people with physical challenges and other underrepresented groups.

Today’s conference is about diversity in storytelling and I am sort of curious about what that word “diversity” means to all of you now. I think that it can mean a lot of different things to different people. We can be talking about diversity in terms of race, we could be talking about cultural diversity. We could be talking about diversity in forms of storytelling. So what does diversity mean to you?

DANIEL JOSÉ OLDER: For me, I think that it’s always important to keep in mind the question of power and a power analysis when we think about diversity. If we’re not careful then, when we call for diversity, we get tokenism, which is what we see happen a lot historically and what we’re still fighting against. So when I think about diversity, when I think about unpacking that word, I try to think about what are the imbalances that have historically gone on, and what are the ones that we face now. And I love that you framed it that way because it really is about, on the one hand, yes, . . . we need to see diverse faces on covers, we need to have diverse characters and we need to have diverse authors, diverse editors, diverse agents. Amidst all that—and that’s already a huge, long road ahead—we need to be able to think about storytelling in new ways. We need to think about rhythm in different ways. We need to think about how we think about and structure narratives in ways that aren’t white and that are not, you know, the same thing that we’ve been doing for a long time. How do we lift up those narratives and those voices and usually it means having really difficult conversations like the one I think that we are starting here tonight.

DR. CHARLES JOHNSON: I think that in terms of the question that you posed, we have a situation in our literature that is almost catastrophic in terms of closing children of color outside the realms of the imagination. As a writer, my primary interest is in telling a good story. And my daughter and I started the Emery Jones series in 2012 when she came to me and she said, ‘Daddy why don’t you want to do a children’s story with me?’ I said ‘I would love to, but what’s the story?’ So she wanted to work with bullies and I wanted to work with a black child prodigy who I had been thinking about for about thirty years—a ten year old scientific whiz kid. So we combined our imaginations and produced a first book which is called Bending Time and we just finished the second, which is called the Hard Problem, which should be out next month. For me, first and foremost, I want stories that are like the ones that lifted my imagination when I was a child. Stories like magic carpets that opened up my mind and my spirit. But further, I want the series that we are working on to nurture the interest in STEM education and STEM fields, science, technology, engineering and math. So those are the kind of things that I am interested in right now in terms of narrative and storytelling.

ELISHEBA JOHNSON: If I can just kind of piggy back on that. Raising a young black male in America right now, I think it is important for him to see images of himself in art. I’m a proponent of STEM, but I think that he needs to see himself on TV, in movies, in the books that he reads and it needs to be different manifestations of what he can be. Not just a musician or a football player, but also a scientist or a dancer or an actor. And so, I think that the more images kids of color have that look like them to tell them the possibilities of what they can be, is really important.

LEILA GÓMEZ WOOLLEY: For me, when I think of diversity, right away I go back to the 1950s and living in an area where I felt totally isolated because I didn’t see anyone like myself. And being pointed out as being "the brown bean" and called every other name that you could think of. Diversity should be where you reach a point where you are totally happy with who you are and it doesn’t really matter what anyone else says and it is a kind of acceptance. Children should have models that look like them, that they can emulate so they feel that there are no limitations and they can do whatever they want.

DANETTE VIGILANTE: When I was a kid growing up, I was a very poor reader. I went to the library and I got better. But in all those books that I read, I never saw a character that looked like me or my friends or my family. That is bad in itself, but what is even worse is that I never really expected to see someone like that. And that kills me. And it goes even deeper. I think that if a child doesn’t see themselves in a book, or in some other positive way as they are growing up, it has an effect on them. And it might not show up immediately, but it might affect their self confidence, in feeling am I not good enough. And I think that’s a terrible thing. And so when I think about diversity now, I kind of think of it like a vitamin. The more diversity that a child sees, like a vitamin taken regularly, it does something good to your body and to your soul.

TRACEY BAPTISTE: I think for me, it is about authenticity. I come from a multi-ethnic family. My father is Indian, my mother is Black and Hispanic. I would like to see families that are like my family. I think that in a lot of ways some of what we’re trying to do now, which is great, is make sure that we are being more inclusive. But I’m not seeing all of the families that I grew up with in Trinidad, where there were so many different kinds of people all in one family and it was a family. That’s something that I want to see more of.

OLUGBEMISOLA RHUDAY-PERKOVICH: Thank you. Danette, you brought up something that I would like to go into, in talking about seeing representations of yourself. Let’s talk a little bit about diversity in the storyteller. In The Color of Children’s Literature, Gene Luen Yang wrote: “Our job as writers is to step outside of ourselves and to encourage readers to do the same.” In the article The Color of Comic Books, he talked a little bit about a young black boy, Dwayne McDuffie, who was inspired by the comic book character, The Black Panther. This character was created by a white man and it did have some problematic imagery and baggage. Mr. Yang points out that McDuffie, at eleven, didn’t see those issues. He just saw this character and was inspired by this and he went on to start Milestone Media, his own company. And Gene Luen Yang says himself that he was inspired by Asian characters that were created by non-Asians. On the other hand, there are a lot of challenges to the idea of writing outside of your experience and sort of figuring out what that really means. Some say it is a matter of doing your homework and doing your research. Daniel, you said it is more than just that. Others say that because of the systematic marginalization of different groups, that outsider efforts should really be focused on amplifying voices of the members of the groups themselves. So how do you all feel about the issue of writing outside of your experience? What does diversity of the storyteller mean? Can it also be someone who has been sighted all their life writing about a blind person? What does that mean?

DR. CHARLES JOHNSON: Can I jump in?

OLUGBEMISOLA RHUDAY-PERKOVICH: Yes.

DR. CHARLES JOHNSON: I really like what Gene Yang speaks. It came as a surprise when we were putting this issue together. It was Rita Williams-Garcia who brought it to my attention and got it from his agent. And I am an old comics guy myself. I grew up reading those same comics that Dwayne McDuffie did. I love the artists, Jack Kirby and Stan Lee. But here’s the point I want to make. As people of color, and specifically as black people, we are bicultural. We grow up knowing that we have to learn how to read all of the signs and symbols and meanings in the dominant culture. And in order to get through school, social situations and jobs, we have to be conversant with that. We also know our own history, which has been marginalized and pushed out of the history books, told to us by family members and so forth. So we are at least bicultural by the time we are seven or eight, nine, ten years old. I think it is to our advantage, as Gene Yang says, to be able to imagine oneself in the shoes of the other, the racial other, the gender other, of the disabled other, of any other. And that takes a great deal of risk, as he says, but the payoff is well worth it. That’s all I have to say.

OLUGBEMISOLA RHUDAY-PERKOVICH: Thank you. Would anyone else like to comment?

TRACEY BAPTISTE: I think you look at a book like The Indian in the Cupboard by the British writer Lynne Reid Banks. That’s the only one that comes to mind at the moment. You know, obviously this novel was written by someone writing outside of their culture. At the time that it came out in 1980, I think that it was acceptable and people were perfectly fine with it. But a certain segment of the population was not okay with it. People recognize that now. I had a discussion recently with some other authors about when you look back at some of these children's books now as an adult. As you are reading these books to your kids, what do you do when you come up with these racist elements? Do you talk about it? Do you pretend you didn’t see it? Do you move on to another book? I think that it can be difficult and if you are a person who is writing outside of your culture, you have to know that culture really well. I don’t think that it is impossible to do it, but it has to be a culture that you know intimately in some ways so that you can do it justice.

LAURA PEGRAM: Since we touched on The Indian in the Cupboard, we may want to ask one of the Native authors that are appearing virtually to comment. Would any of you like to respond to this question on writing outside of your experience?

SARAH CORTEZ: Alrighty. I would just like to respond in a big-picture way to the issue. I think the whole idea that the writer doesn’t have the right or the ability or the skill to write a person from another culture is a really troublesome assumption. I’ve been to conferences where someone who isn’t of my culture, however you want to define my culture, will say you don’t have the right to write a fictional figure in my culture. I just find that very very troubling. I would like to go back to one of the comments that was made by Dr. Johnson that I thought was beautiful, which centered on 'stories that opened up his mind and opened up his spirit.' I do think that there is no such thing as a perfect book. I think that there is no such thing as a perfectly written fictional character. I think most of us, whether we are editors, agents or writers try really really really hard, hopefully with a lot of integrity and a lot of heart and a lot of research, to do what we do.

KARA STEWART: Can I speak specifically to The Indian in the Cupboard? I kind of tend to agree with a lot of the thought on books that have been published several decades ago (like Lynne Reid Banks book for example), books published this decade, even books that are coming out now. There are a number of them that I find problematic in the stereotyping they do of First People, and it seems like a lot of the authors who get into this mire of not portraying Native people accurately are not Native themselves. I have lost video with you, so I can’t see the speakers on the stage. But one of the authors on the panel said people need to know the culture intimately in order to give accurate representations. I do agree with that. The picture that books like Indian in the Cupboard give of Native people is damaging to Indian children because they grow up thinking ‘what is this Indian person being written about in this book? It has nothing to do with me or my family. I know that I’m Indian.’ It contributes to a lot of identity issues. As far as people who are not really familiar with Indian culture writing about Indian people, that makes me a little nervous.

ANDREA L. ROGERS: I would love to add something to the conversation, if I could. Is that okay? I think one of the most powerful things that I’ve heard all year was the culinary historian, Michael Twitty who writes the blog Afroculinaria. I was listening to his talk on culinary justice and the appropriation of cultures. He was specifically talking about food, but what he said was ‘when you were oppressed, how you survived your oppression is a form of capital, and how that capital gets spent is essential to your progress. So what happens when that capital gets appropriated?’ And so I think that is something that we also have to be wary of when we’re writers and trying to be sensitive to other cultures. Sometimes people want to tell their own story and they may have several stories. Thank you.

DANIEL JOSÉ OLDER: I love that point, Andrea and I want to jump in right there. I used to work in this neighborhood as a paramedic. Time and time again, we would go up into the projects where there would be an old guy dying in poverty, with grammy award winning albums on the wall that he had played on. Jazz. We have a dynamic in this country, as we always have, where folks of color, usually black folks—who are the inventors of different aesthetics that are American aesthetics—are dying in poverty while white folks are making millions of dollars off it. That’s a dynamic we always have to have at the forefront of this conversation, because it’s not just who has the right to tell stories. We all have the right to tell stories and we all have to tell stories. And as writers, we are always writing the other. There is no way to not do that. At the same time, we have to be conscious of cultural capital, who makes money off whose story. All those things are so relevant to this conversation and often get left behind because, you know, we’ll be waylaid by different people getting offended sometimes at the idea of censorship. So how do you get into writing the other? How do you have these conversations and think about power? I know for me, it begins with what Junot Diaz said which was: when you are writing about someone else—he was talking specifically about when you are a man writing about women—the baseline is you suck. (audience laughter) And that’s so true. And so absolutely, we all have to write about the other. And absolutely, we have to do it carefully and do our homework. And then we have to go beyond that and realize that we suck (audience laughter), and do it from a humble place of listening. Beyond that, be clear on what the cultural context is of the work that we are putting out into the world because so often there is a cultural context of oppression, whether it is in the publishing industry, in literature or in the music world.

OLUGBEMISOLA RHUDAY-PERKOVICH: Thank you. So we were just talking a little bit about power and I was at a panel on Sunday, celebrating Martin Luther King Day and there was a conversation about whether the vote was still an effective change making tool. And Charles Rangel was there and his point was that yes, power does not give up anything unless it is forced to. So I want to know how do you all think this industry can change? Is it a matter of just bringing more voices to the table? Is it a matter of flipping the table over and creating something new? And what do you think would be put in its place? Who wants to start?

TRACEY BAPTISTE: Where is Cheryl Hudson? Cheryl should talk about that.

OLUGBEMISOLA RHUDAY-PERKOVICH: I'm going to ask the industry pros too.

TRACEY BAPTISTE: I think that there are a lot of publishers like Cheryl Hudson, Wade Hudson and Eileen Robinson at F1rstPages who are starting their own companies because they want to have a seat at the table. Who was it? I think it was Elizabeth Warren who said that if you don’t have a seat at the table, you’re probably on the menu. (audience laughter) I mean, they’re right. There are a lot of publishers that are really making an effort to be the head of their own companies and to see these things come to fruition. But I think that we all know there is more than just that. The percentage of non-white editors and agents in the industry is extremely low. I think that it is actually lower than non-white writers. It is also a matter of mentorship. It is a matter of bringing people in. You see that there is a problem and you bring people in. I think that is one of the ways to get there. I think that it is a slow way to get there, but it is one way.

OLUGBEMISOLA RHUDAY-PERKOVICH: Thank you. Anyone else want to jump in?

DANIEL JOSÉ OLDER: I mean, flip the table. Shoot. (audience laughter) I think that it is what you said. There are so many ways and right now, we are living in an unprecedented time in terms of what it means to be a writer and publishing at all, in terms of social media. As much as it can be a pain in the butt sometimes, it has also given us access to readers in ways that writers have never had before. We have the ability to talk to thousands and thousands of people at the blink of an eye and that’s a brand new thing. That’s the way that technology is changing publishing. So that means there are that many roads to “making it.” And it requires us, I think, to be more creative, in our endeavors both as artists and as publicity people and being who we are in the industry. So I think that there is room to go the traditional route and there is room to go other routes and that’s exciting. I think it does require courage from all ends of the industry, people speaking out, people doing mentorship and taking people under their wings and people being loud, on different levels, and being strategic. So there is no one answer, but I think that’s a good thing.

LEILA GÓMEZ WOOLLEY: I kind of feel that we are very much aware that the population is changing and that with the increase in number of people of color, that publishing has to change. I mean, as long as we dominate the market, it has to be that way. It is just a matter of time, is the way that I see it.

OLUGBEMISOLA RHUDAY-PERKOVICH: Would any of our Skype guests like to jump in on that one?

ELISHEBA JOHNSON: I don’t know if this completely answers your question. But I think there needs to be a radical shift because there are more people of color in America and the dominant culture is going to constantly make films and publish books that they feel represent their point of view or what is comfortable for them. I think that we have to publish our own books, buy books by people of color, have our own bookstores, start our own banks again. I mean, I think that we need to start supporting each other and showing everybody else, by our dollars, how we want to spend our own money. That we don’t want to go see American Sniper, that we want to see Selma. And I think that is where the shift is going, . . . that’s when the big publishing companies are going to change and see well, everybody is buying this book, I want to buy it. I think it has to be a grassroots type of thing.

OLUGBEMISOLA RHUDAY-PERKOVICH: Thank you.

LAURA PEGRAM: Can you say a few words about the second book in the series that is coming out next month?

ELISHEBA JOHNSON: Sure. It is really exciting for us. We finished the first book about a year and a half ago and then started working on the second one. Building on a series, we were able to take the characters we had already developed and go further and deeper. A lot of them have similarities to me and my father. I don’t want to say too much, but they kind of went back into the triassic period in the first book. And now we are building off some things that happened in the first book. But it has been fun. I’ve been able to explore my younger self and kind of heal the nerd in me by having this character. I think it is kind of cool to write about her.

DR. CHARLES JOHNSON: And let me just jump in and say that Elisheba and I are very new to children’s literature and we’re in the company of and sharing a virtual stage with veterans of children’s literature. So it is a great pleasure and honor for us to be able to participate with you. So thank you.

OLUGBEMISOLA RHUDAY-PERKOVICH: Thank you. Okay, one more question. So I would love to hear from each of you what’s coming up, what’s next. And if you could recommend one craft tool—a book, a conference, a person—something that can help people looking to be published or looking to publish themselves right now in children’s literature.

DANETTE VIGILANTE: What’s coming up for me, I’m revising something that I wrote a long time ago before I was even published and it is terrible. And I am ripping it apart, but that’s great because it shows growth. But when I was looking to be published, I had my highlighter and my post-its and I would go through the Children’s Book Market that came out every year. I had to have it and I went through it page by page and highlighted things and I think that was very important. It’s a good place to start.

TRACEY BAPTISTE: I would recommend that everybody go to a conference. Conferences are great places to meet other writers. You get to see people on a very personal level and have conversations and learn the kinds of things that you are not going to learn when you do your research at the library, which you should do as well. There are always editors there, there are always writers. You are among book people and everybody is relaxed and everybody wants to chat about it. I’m in the same place as Danette, where I am trying to revise something and it is butt ugly. (audience laugher) You know it is always there at the beginning and you just slog through it. You cry yourself to sleep a few times. You complain to your family about it and then you just keep on slogging through. That’s all.

LEILA GÓMEZ WOOLLEY: I guess that I’m in a unique position because I haven’t published my graphic memoir yet. Some of you have seen the artwork for Los Pirineos that is in the gallery. Los Pirineos has been in the making since I was a child, since I started writing a journal about living in this country. I'm very fortunate to have a daughter who is an illustrator and who fell in love with the story, otherwise it would not be where it is now. So we are now in the process of getting it published.

DANIEL JOSÉ OLDER: Earlier this month, my first novel came out. It’s not for kids. It’s called Half-Resurrection Blues and we just got word that it was optioned. So that’s exciting. Yay. It’s an urban fantasy book about a half dead guy running around Brooklyn fighting ghosts. So that’s really great. I’m really happy about that. I’m working on the sequel and about to start the third. Shadowshaper comes out in June. And for a book that I would recommend? Actually, Cheryl Klein is here. She’s my editor at Scholastic and her book, Second Sight, which is about editing, is fantastic. It is a really insightful, analytical guide. Definitely check that out.

OLUGBEMISOLA RHUDAY-PERKOVICH: Would any of our Skype guests like to share?

SARAH CORTEZ: I’m not sure if everyone is familiar with Austin Kleon, but his first book, Steal Like an Artist, was really helpful, I thought. Although when you’re Native, you have to be aware that you steal like an artist with honor. So make sure that you honor who you are borrowing from in ways that some people are not familiar with. And then his second book Show Your Worth is the sequel. It is what to do after you’ve written something that you love and that you want other people to see. So those are the two books that have really helped me over the last three years.

OLUGBEMISOLA RHUDAY-PERKOVICH: Thank you all so much. It was a lot of fun talking and listening to you and I appreciate it.