Kuwento: Lost Things began in 2011 as a search, an obsession, a need to excavate the stories our families told us of anitos (deities) and engkantos (spirits). When co-editor Rachelle Cruz and I first indulged in the idea of curating an anthology on Philippine myths, we were struck at how diverse and varied the retellings were: Was the Aswang a bat-like vampire woman? Or was she a shape-shifting beast, or a giant black bird with a long, fetus-eating tongue? We understood that the stories passed on to us from our fathers and mothers were varied but also culturally inherited. It was as if our bodies knew them, and knew them well. As Cristina Pantoja Hidalgo said, “… though the body of tales being produced today remains small, the tales themselves are extraordinarily varied” (New Tales for Old).

We brainstormed a list of titles that almost reads like a poem:

Book of Anagolay and Lost Things

Creating Kuwentos

Lakambini

Book of Alamat

Philippine Pantheon of Kuwento

Invoking Anitos, Invoking the Gods

Malakas and Maganda

Writing Alamat

Book of Kuwentos

Book of Lost Things

Philippine Pantheon of Kuwento cracked us up. But that ostentatious and possible title pushed us closer to the anthology’s heart, its genesis. As we kept probing and digging within ourselves to uncover a name that would reflect the deeply intricate and lush well that is Philippine mythology—mythology that was birthed in the homeland and carried out into the diaspora—we found that the anthology’s essence hinged on what our parents, our ancestors, naturally performed for us at our bedtimes, at the dinner table, during our childhood years: telling us a story. We wanted to emphasize that this collection of Philippine myths was an inclination toward storytelling, of retelling, of re-shifting stories of lore in modern times, an activity that all families, all cultures participate in. This sentiment, this passing of knowledge, of culture, of re-imagined self was encompassed in the word “kuwento,” the Tagalog word for “story.”

So, we began our four-year journey of collecting poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and visual art that ultimately told us a compelling story doused in Philippine folklore andor myth. We sought work that challenged our old perceptions of Philippine mythology, seeking stories and poems that were fresh and enticing, seducing and mythical in their own imagination and recreation. We realized, then, that “kuwento” captured only half of the anthology’s essence, and that the other part, its center, was “anagolay,” the feminine “anito” for lost things. We first sought to “reclaim” old myths from our cultural heritage; but through the organic process of curation both within and without the homeland and the diaspora, we found that many of our contributors were doing so much more than re-claiming; they were making anew what was once “lost.”

It is better said by Elaine Castillo, whose powerful voice ends our anthology:

"The Philippine mythology I came across thought the santelmo was the lost soul: the one drowned in the sea, aided by no one; the one who died before her time, and thereafter spent eternity enticing others into similar untimely deaths. ... The only thing I still can’t figure out is if I’m the santelmo herself—the one lost, the one whose history works just like a horror story, the one whose vengeful flesh will be broken down, denatured, and then, maybe, preserved. Or if I’m the witness, the one being pursued by the santelmo—the one full of questions, the one whose faith isn’t always strong enough, the one who travels alone, the one who reaches for the bitter charm, the one at risk, the one who still might have a chance." (206)

Castillo’s haunting and universally desperate predicament reflects the beating heart of the anthology: Aren’t we all like the santelmo, a lost soul, one who is drowning at sea, one in need of answers? It is with this book we hope the invocation of the past is somehow answered, somehow quelled, somehow excavated, and thus reborn—reborn in our own terms, in our own myths, in our own kuwentos.

To celebrate the anthology, we’re having an official East Coast book launch at the Asian American Writers’ Workshop on July 9th, 7pm. We hope to see you there

OFFICIAL EAST COAST LAUNCH

Presented by the Asian American Writers’ Workshop

EXCAVATING "NEW" PHILIPPINE MYTHS--KUWENTO: LOST THINGS

with Anna Alves, Sarah Gambito, Jessica Hagedorn & Melissa R. Sipin

Thursday, July 9, 2015 7:00pm

Asian American Writers' Workshop

112 West 27th Street, 6th floor

New York, NY 10001

RSVP:

http://aaww.org/curation/kuwento-new-philippine-myths

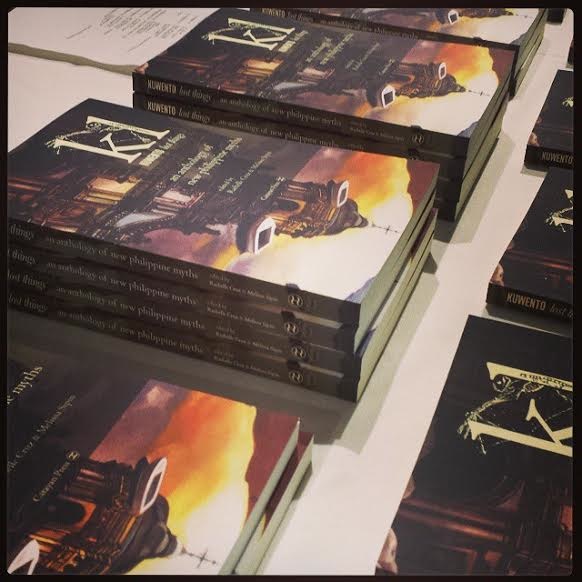

Join us for a special event celebrating a new anthology of Filipino myths: Kuwento: Lost Things. We’ll hear from three contributors from the anthology: Anna Alves, Ph.D. student in American Studies at Rutgers University, Newark; Sarah Gambito, cofounder of Kundiman; and Melissa R. Sipin, co-editor of Kuwento. Moderated by acclaimed novelist Jessica Hagedorn, author of Toxicology and a winner of the AAWW Lifetime Achievement Award.

Co-sponsored by TAYO, Kweli Journal, the AASP at Hunter College, and the Hunter College NEH Summer Seminar for School Teachers: Asian Americans in New York: Film & Literature.

Image titled "Fishers of Men," by Eliseo Art Silva.

Batibot: small but terrible. Melissa R. Sipin is a writer from Carson, Calif. She published her first short story in Kweli Journal. She then went on to win Glimmer Train’s Fiction Open and the Washington Square Review’s Flash Fiction Prize. She co-edited Kuwento: Lost Things, an anthology on new Philippine myths by Carayan Press, and her work is in Glimmer Train, Guernica, ON SQU, PANK Magazine, Hyphen Magazine, Midnight Breakfast, and Eleven Eleven, among others. Melissa cofounded TAYO Literary Magazine and teaches at Old Dominion University.