guest-edited by Jennine Capó Crucet

The four of us live on the rooftop, in the azotea of the building where we work. It's a four story building in the San Miguel Chapultepec neighborhood in Mexico City. There are four families in the building: a family on each floor, a maid for each apartment. One María for each family.

Our little world is surrounded by treetops and buildings, our four little rooms one next to the other on the same rooftop where we hang laundry to dry, where the propane cylinders are lined up along a short parapet wall, where the water reservoirs sit like white whales, and thin aluminum television antennas no one uses anymore swing like weather vanes whenever the wind gusts. Up here the rain falls first, the sounds of the street, cars, and people rises with the heat of the day. Up here, the four of us sit on hard wood chairs late at night and watch telenovelas in Silent María’s little black and white television. Four maids serving the four apartments below. Now we’re just three.

I am María. And so is the one in the blue-checkered uniform with the white apron. We call her Lucky María because she has a pretty singing voice and is from Cuautla, which is not far from the city so every other Sunday she can take the bus home and see her family. The older María, the short dark one that lives in the last room, is María from Oaxaca. She’s serious. Quiet. We call her Silent María. And then there is the dead one, the one they found this morning. She’s also María. She was young, pretty. We called her María la Bonita from Chilpancingo. Now she’s Dead María. María la Muerta.

What happened to her, well, it happens. What can anyone do about love?

The people we work for call us from their windows. If they’re desperate they yell for us from the back stairs. But we spend most of our time in their apartments, cooking and cleaning. If they call us, it’s usually in the afternoons when we’re hand washing or hanging laundry, or late at night.

We recognize their voices by how loud they are. We know the urgency of the demand by the pitch. Most of the time it’s an emergency: to meet the children at the bus stop, to run to the market and get limes or tortillas, to help them find their socks or the remote for the large television, to make a late snack. There is always something: María, my mother says to come down and start dinner because we’re going to the movies tonight. María, Antonio came home drunk last night and got sick all over the floor and my mother wants you to come down and clean it up right away.

María. María. María. María!

At dawn that day, I heard Lucky María sing a pretty song. Her voice carried across the rooftop like a pleasant breeze. Silent María was already downstairs attending to the children of the family she worked for, waking the children, dressing them, feeding them before sending them off to school.

La Señora Vázquez, the woman whom María la Bonita worked for, called for her at quarter to seven. María la Bonita was already supposed to have been down in the apartment cooking breakfast for the family. But she hadn’t showed up. Now la Señora yelled for her from the window of the second floor. “María!”

La Señora went on like that for forty-five minutes. “María! Get down here this instant, niña.” And, “María, by God, what is the matter with you?” And “María, El Señor has to go to work.” Her voice had a raw, desperate anger.

I went to check on María La Bonita. I knocked on the door and waited. When she didn't answer, I pushed it open and found her lifeless body laying in a pool of her own blood, dark and still like a lake on a windless night.

The police will blame Miguel, the young man who works at Panadería Hércules, a little bakery two blocks from here. Miguel was María's lover.

We're invisible. We cook and clean and nod and smile to the people who give us a paycheck every fifteen days. We send most of the money to our parents in our hometowns where they are so poor they have to walk for miles to get water or take a microbus to visit the doctor.

I left school at nine and came here to work after I turned fifteen. But I'm lucky. I'm helping my little brother go to school. I pay for his textbooks and uniforms. I help my parents. Gabriel does not have to work and take care of the goats and the milpa. He can focus on his studies. I do all this out of the goodness of my heart because I love my family. And this way Gabriel will have better opportunities than the rest of us.

María la Bonita once told me her father sent her to La Capital to work because she liked to be with her friends. She didn't say it, but I knew she meant boys. I'm not dumb. She was pretty and had a way about her that you knew attracted boys. Like a young Veronica Castro. She had that style, the one that lets everyone around her know that she knew she was pretty. She didn't say this, but I think she used it to get her job with the Vázquez family because that was how the old man was. La Señora's husband liked pretty maids working in his house.

Lucky María was not so lucky before she came here. She told us how her father's compadre came into her room and forced her to do the things you're supposed to do for love, the things you keep for your husband. She was twelve. At fourteen her mother sent her here to work. She worked for a rich family who lived in a big house in Lomas de las Palmas. They had three maids and a chauffer. Then one of the boys there took advantage of her and she left. That is how she came here. The Magaña family on the third floor had lost their maid when she married one of the propane deliverymen and moved to Ciudad Neza. Her name wasn't María.

I'm friends with a woman from my pueblo in Guerrero who works across the street from the house where Lucky María worked in Palmas, and she told me what had happened and that the poor girl needed a place to live and work, so I told her about the Magañas who lived on the third floor.

Lucky María sang every morning at five. She sang softly at first, then her voice rose with the sun. She sang while she showered and watered our little garden of medicinal herbs: yerba buena, hoja santa, manzanilla, aloe. She sang songs we had all heard before: Amor de Alma, Échame a Mí la Culpa, Directo al Corazón, Cielito Lindo. But she sang them so beautifully, so vivid and full of pain, that they became her songs. And ours.

Lucky María made life pleasant for us. Mornings were the most beautiful part of our day, unless we happened to be on the roof when she hung laundry. Lucky María sang like a bird, like one of the little canaries the men in Chapultepec Zoo keep in cages. You pay them a few pesos, they open the door of the cage and the birds hop out and choose a fortune for you from a little box.

I think that's what María la Bonita did: she chose her fortune, only she was too young to know the consequences. María, so young and beautiful but not so innocent that she lost sight of what was important. Sometimes you find yourself between God and the devil and you're forced to make a choice.

The police came. I told them what I knew. María la Bonita had worked here for just over a year. She never got into any trouble. Not with the Vázquez family or anyone else. All four of us felt we were in a place that God had given us and we accepted that, except perhaps Silent María who had her own ghosts.

I had to tell them about Miguel. I knew the police were going to question him. He had no way out. He's young and poor and we all know how that goes. They will take him away, find him guilty, and send him to Almoloya or whatever prison where there's room for another doomed soul. But I don't think he's to blame. I have met Miguel's mother at the panadería and she was pleasant and cordial. Miguel had also always been that way with me. He had been brought up well, humble, with manners.

Maybe María la Bonita went too far. In the last few months María la Bonita had told me she and Miguel would get together on her days off. She said they'd walk around Chapultepec park and share nieves and row a boat around the little lake, and that he once offered to have her fortune told by the men with the little birds.

She said they sometimes found quiet spots under the ancient trees and listened to the whistles of the balloon vendors and the bells of the ice cream carts. They'd lay in the cool grass and look up at the sky and at the Castillo, the old castle that jutted out at the top of the hill. He would tickle her face with a leaf, then lean over her and press his lips against hers. One day she parted her lips and let him in.

Everyone thought Dead María had done what she had done to herself because she wanted to stop the impossible, something a man had started and only she could finish. And this is what the police investigating the death of Dead María will be asking Miguel, to make the case that it had been he who got her pregnant. But it had been Silent María who confessed that we all have secrets. Then she admitted that Dead María had not been pregnant.

That morning there were more people on the roof than I had ever seen. Our world was invaded by the families from below, people from the street, paramedics, the police.

I thought of Miguel. Then I noticed the handsome Vázquez boy who comes home drunk every weekend standing behind the short man who had come with the ambulance. He kept to the rear near the stairs as if he didn't want to be noticed. But I noticed. And I noticed his eyes.

Later, his mother, la Señora Vázquez, finally appeared. She walked around the rooftop as if she owned the place, and I guess she did. But there was more than that. It was as if she owned all of us, even the medics who were wrapping Dead María in a white sheet, and the police, and even the family from the third floor who had also come up to watch.

La Señora marched right up and studied María's lifeless body, as if to make sure she was dead. Then she looked around the room as if something had been stolen from her. I thought of the four of us here and our little lives, but all that is irrelevant because really, when you're a María what do you have?

La Señora stepped out of Dead María's little room and glanced over the crowd just standing there, doing nothing, staring. Then, La Señora stomped toward the back stairs, every one of her steps a loud protest I didn't understand until she turned to her handsome son, whose tears had dried on his cheeks, and said, "Carajo. Now we have to find another maid."

Contributor Notes

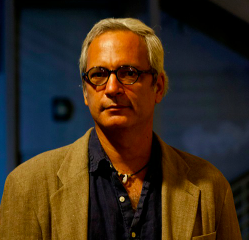

Phillippe Diederich is a Haitian-American writer and photographer born in the Dominican Republic and raised in Mexico City and Miami. His short fiction has been awarded the 2013 Chris O’Malley Fiction Prize from The Madison Review, the Association of Writing Programs Intro Journal Award for fiction, and received two Pushcart nominations. His stories have appeared in The Acentos Review, Quarterly West, High Desert Journal, Hobart, Frostwriting, The Wisconsin Review, and many others. He is the author of Communism and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, an eBook that includes an essay and forty black and white photographs of Cuban Harley-Davidson bikers in Havana, Cuba. His first novel, Sofrito, will be published in the spring of 2015 by Cinco Puntos Press.