Nonfiction

I turned over on the thin straw mat, still drunk from the Makali rice wine.

“Il-un-na! Il-un-na!” my Um-ma said as she smacked my bare legs. I was stunned. My mother woke me that Tuesday morning with a coarseness that I wasn't used to.

“Um-ma, what's the matter?” I asked in Hangul while digging into my lopsided Afro to scratch my scalp.

I played innocent. But I started to wonder if I’d been found out. It wouldn't have been the first time. Um-ma had many eyes in Bupyeong. A few weeks ago she found out that I stole a bicycle outside of town to joyride with the T-Shirt Alley boys. The Drunk, Stinky and Kim Soo were homeless and had nobody to answer to. But I got the end of the broom for that one. Last night I was careful. I was a true slickyboy, lifting a mug of Makali rice wine from the only local Korean bar that served commoners instead of American GIs. Running all the way to the bridge without being seen by any of Um-ma's spies, and without spilling a single drop.

Um-ma’s Buddha smiled down on me last night.

But that smile disappeared come morning.

I heard the bugle play morning colors. It had been two years since we moved to Bupyeong and I still wasn't used to that brass rooster from Camp Market. The bugle from the military base signaled Um-ma's return home at 5 a.m. each morning. We lived in a small studio apartment, directly above Un Sook's all night restaurant. Um-ma worked nights, slept during the day and didn't wake up until noon. I was only eight, but I kept about the same hours as my Um-ma, running with the T-Shirt Alley boys all night, begging for food, drinking wine on the bridge, before climbing into bed an hour or two before she got home. I never went to school. A Cumdingi was not welcome anywhere in South Korea.

“Where are we going?” I asked.

Um-ma sat at the vanity now and applied the finishing touches to her green eye shadow. "Orphanage!” she snapped. “Now pack a bag." Um-ma did not look at me when she spoke.

There was something in her voice that morning. I couldn’t name it. It wasn’t the fear that gripped her throat in T-Shirt Alley some weeks ago, on the night of the police raid. Then, she wasn’t tipped off; she couldn’t take me to an orphanage in advance. She sat shackled with the other women and yelled at me from the back of the police van. “Stay at home for the next two weeks! Don’t go anywhere! Eat downstairs and be a good boy! I’ll be home in two weeks! Sa-rang-hae-yo! I love you! You are my little man!”

The voice this morning was different. Sharp at the edges. I sat straight up on the floor mat. Stared at her. Her straight black hair was curled up tight like my Afro. But other than the tight curls, Um-ma and I looked nothing alike. I resembled the Apogee I had never met, but always imagined. In my mind, my father was tall, brown, with biceps bulging, dressed in pressed Army fatigues. Smiling. I was a short, muscular Amerasian kid with brown skin and large, round Asian eyes. And my Um-ma was a South Korean woman with stubby arms and legs. A long torso. She moved as if still wet, as if she had just come home from working in the rice paddies, with cotton pants clinging to her skin. Her new work clothes now rested at her feet: a short dress and black fishnet stockings. High heels. I got up and rolled the thin mat before tucking it under her bed. I knew the routine, so I started packing for the orphanage.

I had been to many orphanages in Bupyeong before, so this was nothing new. Um-ma would periodically drop me off at an orphanage before a scheduled raid or forced quarantine, then pick me up a few days or weeks later. I went out to the back porch in my underpants and rinsed myself off with the water hose, then dressed. I found my bag and gathered some clothes: two pairs of brown pants, three button-up blue and white shirts, three pairs of underwear and two pairs of grey socks. I stuffed them into the sack. But before I tied the strings, I added my tattered black velvet bag of Ddakjis. I never traveled anywhere without them.

Just below us, I could hear groups of soldiers as they marched and sang. I had a limited command of English, but I could make out some words. The few words of English I did understand I learned from my Um-ma and the soldiers she introduced as her boyfriends. Mr. Jones was Um-ma’s steady friend and the only one ever invited into our studio apartment on the second floor. He was brown with an Afro an inch high. He introduced me to the words, “Fig Newtons,” “Oreos” and “Coca-Cola.” They became bribe and bounty. I was often allowed to take a pack of Fig Newtons outside with me so Mr. Jones and Um-ma could talk in private. There I studied the GIs that moved freely through T-Shirt Alley. There I dreamed about my Apogee marching among the soldiers and smiling at me. Now they poured out of the gates of the military base, marching down the street in unison with rifles resting on their shoulders. I watched them from the window in their white gloves and netted helmets. Then I watched the massive camouflaged trucks, covered with green khaki netting, as they crawled out of the gates packed with soldiers and supplies. They roared off in both directions leaving behind clouds of black smoke. The thick smoke lingered in the air long after the trucks left, just like the sing-song voices of the soldiers.

A taxi sat in the black smoke outside our studio apartment for over 35 minutes. Waiting. We climbed in and my mother gave the driver our destination. The taxi driver jammed his cigarette into the ashtray, put the car in gear and mashed the accelerator. We quickly rode out of Bupyeong and left the city and our small studio apartment behind.

Before long, we shared a dirt road with oxen and farmers. It was a bumpy ride and Um-ma and I bounced around on the seat. The road smelled of manure and stretched deep into the countryside through the rice paddies. I watched the familiar sight of women bent over, standing in knee-high water, and I remembered my Um-ma doing the same work a few years ago in the rice paddies of our rural farming community, a day’s walk from the port city of Incheon. After long days in the rice fields, Um-ma came home to the round clay walls and thatched straw roof of our single room hut, smiling at me. We lived there together until the village elders decided that a Black child brought too much shame onto the village and Um-ma and I had to leave.

The feelings of the farm community were no secret. By the time I was four, my ears had already heard their fair share of curses from the adults in the village. “Cumdingi, ge-seki, ship-seki,” they would say whenever I passed. Then they would suck their teeth and dig deep in their throats to produce the appropriate phlegm to spit at my small feet. “Mommy always told me to be respectful to the dying!” I’d yell back at the Ajjoshi and the old Korean women who spit at me. The thirty-some-odd children in the village weren’t much friendlier. I played alone every day, but I always stayed in their vicinity just in case one of them gathered up the courage to ask me to join them and play along. That never happened. We gathered our few belongings into a sack, along with two handfuls of rock salt—the currency in that small village—and left the village with the roosters early one snowy winter morning. Within days, Um-ma found work in Bupyeong, a town outside the capital city of Seoul. And I found my first friends among the crew of homeless kids in T-Shirt Alley: The Drunk, Stinky and Kim Soo.

The whole time we rode in the taxi, my mother stared out of the window deep in thought. Her eyes never seemed to move with the scenery like mine did, but rather stayed fixed on the dirt road. I sat back on the large plastic-covered seat with my feet dangling, while the smell of the driver’s cigarettes pinched my nose. I couldn’t help but wonder what bothered Um-ma. I kept a hold of the door handle with my right hand, and my left held firmly on the seat to keep from bouncing around from the rough ride. I continued to glance at my mother desperately looking for signs that she was feeling better. But she remained quiet as she swayed from side to side. I decided to stay quiet for the remainder of the trip too, speaking only once, about forty-five minutes into the ride, to ask Um-ma about the delightful smell of fresh baking bread as we approached a building that looked like a school.

Contributor Notes

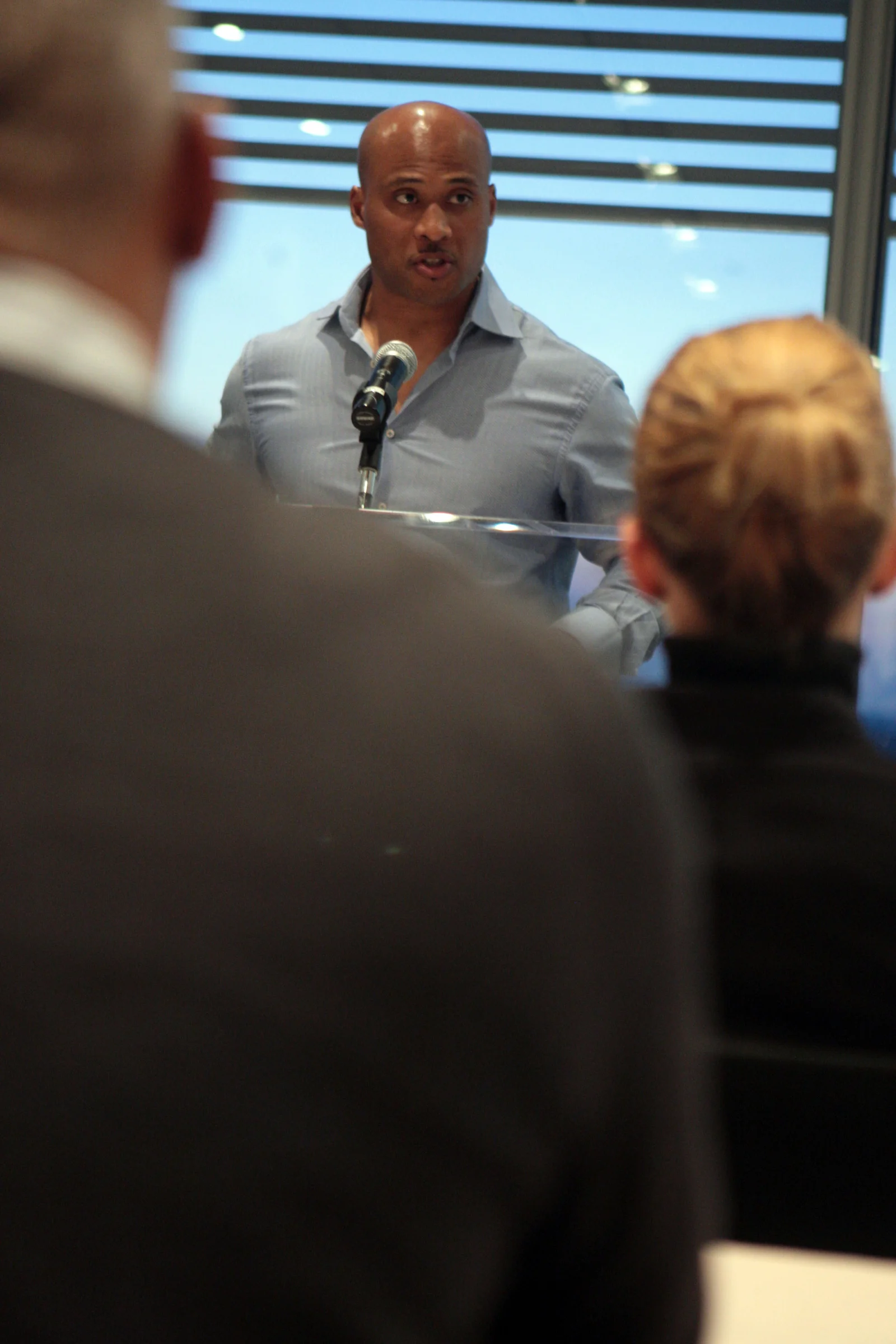

Milton Washington's upcoming Memoir, "Slicky Boy," tells the story of a boy born of a Korean prostitute and a black military service man, living in Korea for the first eight years before being adopted by an African-American family who brought him to the U.S.