After two years in New York city where I had been mistaken for a white man more times than I can count, I finally touched the earth in western Queensland. I had flown for thirty-five hours and traversed almost 16,000 kilometers on three quite different aircraft, the final one a four seat Cessna which landed at the show grounds on a hot and dusty afternoon.

It took an international call to produce a local cab.

“Staying long?” asked the driver.

“Not long,” I replied. But who knew what the truth might really be?

We bounced over the dusty rutted road. Out the window lay the flat country of my ancestors: cracked, brittle, abused and compacted by the hoofs of white men’s cattle. The sky was cloudless and the so-called ‘Wilson’ ranges yawned towards the late afternoon sun. Who was Wilson? Probably a pastoralist, an Englishman, someone they used to call a squatter. My people had lived, loved, and died on this land for an amount of time I could readily recite, even though my mind could not comprehend what 60,000 years might really be. The pastoralists now owned our town, our land, and controlled everything but the rainfall. So, I found some justice in the drought that afternoon, and the chalky skeletons of dead cattle along the line of Mr. Henry Jakob’s ten-kilometer boundary fence.

When Showgrounds Road met Shepherd’s Creek we turned left onto bitumen and followed the course of bone-dry river bed towards the town centre. We passed the abattoir, then the chipped and dented sign ‘Scarlet: Beef Capital of the World,’ its battered condition partly attributable to my cousin Jimmy’s throwing arm. I remembered the hours he and I spent there, chucking stones at that same sign while dreaming, as children do, of fortunes and adventure. Jimmy was long dead, his gleaming smile and handsome black face now only a memory. One which brought a sudden sharp pang of guilt. I remembered his funeral and my uncle sobbing. Then the televised protests at the wake desiring justice for his death—a white male pastoralist ran him off the road and was let free with no charges. That feeling of guilt was tied to my failed attempt to write Jimmy’s story, my inability to articulate his short life so far from home. I also recollected the time my Auntie’s tears fell on my mother’s shoulder as our Native Title claim was thrown out of court. We were called to prove ‘continued customary occupation’ of our own land. We had to convince white law, a bitter joke.

So, this home of mine was weighed down by loss and grief, sometimes beyond endurance. I remembered the shameful joy I felt when I was allowed to leave. No one could blame me for being accepted into the University of Queensland, no more than they would later blame me for going to study in New York, although not even I thought I would escape forever.

This was my home. This was where my mother waited for me.

And there was her old workplace ahead, the local clinic where she had been a nurse, the whitewashed brick building slopping to the right. The foundations rotted from a flash flood when I was only ten. I remembered her crisp pressed uniform—a symbol and point of pride during my childhood. She had been educated, seen the world, returned home.

I knew Mum was also proud of me. Indeed, she was the one who pushed me away—liberated as she saw it—towards writing and eventually New York. She instilled in me a sense of obligation, bound by an ambition far beyond what I had ever imagined for myself. Within the ambition she had thrust upon me grew an insidious fear about how to express the wholeness of something that had barely touched the surface of myself, that of my heritage, my identity, and injustice. And now as we passed the shell of a rusted, abandoned, and lantana ridden Holden Ute on the creek bank, I pondered, what can the writer do? What can stories mean in the attempted distillation of a thing, an emotion, a violent act, a subjugation bound to words like genocide and colonisation? It seemed too weighty a task. Weighty and also wrought with complications; I both admired my mother for protecting me from the harsher elements of our existence and for her ambition for me to speak truth in story (a paradox I am grappling still in writing fiction), but I also felt crushed by the heft of her crusade for me. Still, I was the vessel in which she broke new ground. Her son was the first local Indigenous student to get a scholarship for overseas education. There had been a whole page in the Scarlet Gazette about me. And, even though I had my anxieties about the writing life, to tell the truth, I was pretty proud myself. My time in New York had been transformative. I had read voices from every corner of the world; I had learnt from masters of the writing trade; I had witnessed another troubled history. I wondered whether I could settle in back home. I worried that New York would be stolen from me and I’d be sucked back into the slow rhythm of community, family responsibility, tips of the hat, talk of cattle, guns, and the stolen earth that was my blood, my right, my responsibility.

Motley dogs scratched, fought, and mooched on the creek bank near a few tents and humpies where some of the homeless mob lived. Camp dogs, we called them. They picked up their ears at the hope of food and stared as we drove past.

I saw my Auntie’s house with her bright red spidery Grevillea, flowers that looked sci-fi to my newly acquired New York eye. We passed Romano’s supermarket which an Italian built in the sixties and his son had inherited. There were the butchers, the community centre, and finally, the green brick home where my mother sat waiting and where I would embrace her very soon.

“Drop me at the Royal,” I said, and the driver smiled uncovering yellow rotted teeth.

The Royal Hotel sat in the town’s cluster of power: the shire offices, the post office, the police station and lock-up, the lawyer’s office, the accountants, and the war memorial. I tipped the taxi driver before remembering that wasn’t our custom.

The Royal had two levels. The bottom, where I used to play pool with my cousins, and the second floor where the pastoralists drank. The segregation had not been legally enforced for many years, but the racist custom had persisted.

For the first time in my life I climbed the stairs. It seemed to me I had no choice. I had changed, transformed, been educated. I was the weary international traveller, I was the scholarship winner, I was the writer of growing renown.

This was not the pub I knew, I thought. There were no old photos on the walls down stairs, but there they were, framed with brass inscriptions, Shire Presidents and Engineers with beards and handlebar moustaches, the local cricket team of 1898, 1923, 1954. Yet, for all that, the bar itself felt familiar, with its slightly sticky floor and morning-after smell of stale grog.

A single barkeep stood behind the long-curved bar. I nodded. He stared at me. I dropped my bag.

“Schooner thanks, mate.”

I was not the only customer. The other bloke was Arthur. I had never spoken to him but everybody knew his name. I nodded again. He sat unmoved with his back to the wall and stared at me intently. The afternoon sun cast a shadow cutting his face in two. I could see the punishment his white skin had suffered from the harsh Queensland sun: the cracks and deep lines, the moles and cancer spots covering his cheeks and neck. His stubble was grey, his brow furrowed. The left ear was missing.

His cloudy eyes held me and I prepared myself for trouble.

“Pull up a pew,” he said.

His intention was not clearly friendly, but I brought over my bag and drink and sat down near him at the bar.

“You’re that writer, aren’t you?” he asked.

“One day, hopefully.”

“I saw you in the paper. They made a fuss.”

“They did.”

He put one elbow on the bar and rubbed his stubbled chin.

“You’ve heard about me, Akhurst?”

I did not know his second name. “Mr Arthur?”

His lip curled into a half smile. “You know about my ear? Is that it?”

“No.”

“But you’ve heard them talk about it?”

I’d heard he had been a copper, and a hard one too. I’d heard there was an accusation and a trial when I was only a child but I couldn’t remember the details. I knew that this was a powerful white man in our small community and I felt his gaze strongly and it placed me back. Back into my place.

“You know what they call me?”

“Staffy,” I said. The nickname did not match his hulking physique, but it evoked an old fighting dog with a history of unknown injuries and long forgotten scuffles.

“Buy us a beer?” he asked.

The barkeep was friendly then.

When I pushed the beer along the bar, Staffy rubbed his hands together like a large and raddled praying mantis. Yet, he didn’t lift the glass and drink. Instead, we sat for a time while he rubbed his hands. The pub was very silent and very still. A gust of wind came buffeting the windows with dust. Staffy cleared his throat.

“I’ll tell you the story about my missing ear,” he said, then held his glass with peculiar delicacy, his little finger extended.

“But you need to promise me two things. One, that you’ll keep my glass full, and two, that you’ll one day write my story.”

Enveloped by his stern grey eyes, I suffered a particular fear that had not touched me in two full years. I quickly agreed to both his terms and I bought him another beer before he settled into a slow rhythm of speech that transfixed us both. This is the story he told.

*

You know about the Mabo decision, Akhurst? Yeah, you know that? Fair enough, of course you do. I came to Scarlet one year after that law was finally passed. All the white blokes around here were in an uproar. They thought their land was about to be given to the blacks.

Mabo was 92. I arrived in 93. It wasn’t my first rural posting. I’d done two years up in Aurukun, but the humidity got to me so I looked for something further south. I was ambitious back then, and reckoned I could rise quickly in the force by posting where nobody else wanted to go. To be honest, I wanted another adventure. I was in my twenties and I’d been brought up on Burke and Wills and the Australian spirit of conquering the unknown.

In that first year I witnessed a lost people. I mean your mob, Akhurst, all your Aunties and Uncles, broken with grog and no purpose, forced to watch their land trampled by countless heads of cattle. And it wasn’t just the land they’d lost but the water too, underground water and the river system, pumped and fed into the cattle stations. Sacred sites were pissed on by white teens. Unwritten laws of segregation were enforced by white proprietors. There was tension. Racial, economic, and everything in between. But you see, I was not a monster. I understood where your mob were coming from, but I was also a copper and had a job to do. I was firm with the blackfellas, but I also looked after the younger ones, those I thought still had a chance, you know? And it was on returning from a camping trip with a bunch of kids from the Gum Nut Centre that I met Francis Giles.

Giles was a new recruit in his early twenties and Scarlet was his first posting. He’d come up from Melbourne and had city ideas. He was tall at six foot four, broad shouldered, and preferred the company of books and grog to human beings. The other two officers gave him shit for his massive proportions and his scruffy dark fringe, his hair in violation of code 25A.

The trouble with Giles, from the very start, was he never knew when to shut up. He was a fervent believer in an Australian republic and this was upsetting to local folk who loved the Queen of England, Queen of Australia as she also was. Yet, on he drummed about breaking away from the long shadow of monarchy.

So, there was that.

Then he befriended a black activist by the name of Markus Walker, who was somewhat of a leader to the mob here. The two of them could be seen strolling by the river in the early mornings. The town soon began to whisper and their walks became notorious. I mean, a white copper befriending a black activist? What was discussed along that creek bank? No one knew but they imagined the worst. You could hear the buggers laughing together. Well, Giles lived in Mrs Jarvis’s boarding house and his window was smashed and then his bed was pissed on. I suggested he talk to Walker somewhere a little more private.

He says to me: “Oh, this isn’t personal.”

Jesus. People were sending angry letters to the government, and in general the whites showed him no respect at all.

All the while he was working out this great scheme with Walker, what they called ‘a system of community-based justice.” Instead of locking up blackfella’s for minor offences, Giles worked with Walker on ‘alternative arrangements.” It was not the time or place for this. That was definitely the town’s opinion.

The day in question saw me and Giles overseeing a pastoralist assembly at the Leagues Club. It was all about the Mabo legislation, which made the pastoralists start claiming that the blacks were being favoured by the Labor Government. Now anyone could see that was ignorant, but these were men who owned the country and Mabo was all they could talk about. It was the same amongst the black mob, and it was no coincidence that the blackfellas had gathered for the same reason, on the same day, at the same time, down at the showgrounds.

The whole town was talking about Mabo and what it meant.

The two other officers were posted to the showgrounds. Giles and I got what we thought was the easy job. Whoever expected trouble from pastoralists? Not us. We parked outside the club in the paddy wagon, engine running, air conditioner on. If the windows had been down we might have had some warning before the front doors burst open and a great mob of white blokes surged out into the twilight, cussing and yelling, onto the street heading for showgrounds road.

I wound down my window as Mr Romano passed.

“Where you off to, mate?”

“We’ll give them bloody Mabo.”

I slipped into first gear. We crept along in the paddy wagon as the pastoralists marched, much like they would have done on Anzac Day.

We were still in their midst as we arrived at the showground’s car park and from that vantage looked down at the mass of blackfellas and Walker on stage. Giles observed it was better than a drive-in theatre. I moved us slowly to the front and together, with the white men all around us, we watched Markus Walker as he rolled back and forth on his feet with the microphone in his hand. He was a performer, obviously. Rail thin as he was and small at around five foot eight, he stood tall and beguiled the audience with a voice that carried intent through the light dusk breeze. He addressed the crowd with heightened zeal at the pastoralist’s presence. Squinting into the setting sun he said:

“Scarlet’s apartheid. Scarlet has a black history.”

Giles took off his seatbelt.

“You right?” I asked him, and caught a wildness in his eyes.

“Don’t be thinking about going out there, mate.” I said. “Let this play out.”

Giles pulled up his sleeves.

“I’ll sort this,” he said, and was out the door, slamming his way through the pastoralists, then down the gentle hill onto the flat, through the no-man’s land between the whites and blacks and then in amongst the blackfellas.

I turned off the engine as Walker hit his crescendo.

“White Australia has a black history!”

The whites were deadly quiet. I thought this was on account of Walker, but then realised it was Giles they held their breath for. He was climbing the bloody stage.

“They’ll kill the silly bugger,” I said to myself.

Giles walked towards the speaker with his long arms raised in placation.

Walker was shouting, but he’d turned his mike off so all my intelligence came from the language of his slight frame, his jaw thrust forwards, hands on hips.

Such was the tension in those moments that I thought the slightest noise would bring on war.

Then they stepped toward each other.

They clasped hands, black and white together, and shook.

I can’t say what the crowd felt, but for myself it was considerable relief. I got back into the paddy wagon, turned on the air conditioner, and watched the crowds disperse of their own free will. The pastoralists to their cars and from there to stolen land, the blackfellas to the fringes.

As we patrolled the little town I could see Giles was high on victory. He would have loved to talk about it, but I made that hard for him. He thought he had headed off a brawl, but the blackfellas were still revved up and soon, sooner than later, they would be pissed.

“Quiet night,” said Giles.

I agreed it was, and it stayed that way until about eleven when we came upon Walker and ten or so of his mates. They were in the middle of Cook Street heading straight for the centre of town, camp dogs followed.

I turned on the spotties and approached them slowly from behind. A bottle broke beside us. I turned on the speaker.

“Alright lads, time to head off,” I said.

“Piss off,” was their resounding response.

Giles did not want to radio for help. It was me who had to do it, but good luck with that, we were already outside the Leagues Club. I sat behind the wheel as a young bloke named Sam dropkicked an empty bottle into the front gate. Giles wound down his window.

“Watch yourselves,” he said.

“Or what?” said Sam.

“Markus,” shouted Giles. “Calm them down, will you?”

“Put up your bloody window,” was Walker’s reply.

Giles looked at me with some crazy sort of pity and shook his head.

“No,” he said, and opened his door. “These are my friends.” He closed the door and turned to Walker who took his time sculling the rest of his beer.

“Come on, mate,” said Giles, with a softness.

Walker smiled then.

“Time to go home, hey,” Giles continued.

“Time?” said Walker. He looked down at his empty beer bottle for a moment before firing it through the Leagues Club window.

“Right. Walker, you’re coming with us.”

I grabbed my night stick and stepped out of the wagon. The mob bolted off down the street leaving only Walker, a tiny bloke compared to the massive Giles.

“You and your fucking republic,” said Walker. “Stuff your white republic.”

Why would Walker say that? What sort of mongrel was he? No respect, is what I thought as Giles reached out as if to touch his shoulder.

Walker stepped forward and swung hitting him square on the chin. He stepped back and raised his fists to fight.

Giles touched his face and turned to me. I wondered what the bloody hell did he expect? Certainly not this. Something inside Giles had broken. His face was pale with shock. He wrapped his long arms around the little dancing Walker and slammed him to the ground, and then the cuffs were in his hands and then they were snapped on Walker’s wrists. I had the doors open for him and he threw his prisoner in the wagon hard.

“You right?” I asked.

“Give me the keys,” he said.

He didn’t take us past the supermarket which was the way back to the station. Instead, he drove us past the school and out towards the neighbouring town of Maroon.

“Where we heading?” I asked.

“Won’t be long.”

He drove us onto a dirt track that led to the river. A few minutes later he stopped and we both got out. It was eerie in the dark with the overhanging gums and the moon sparkling off the black water.

Walker stayed pretty quiet as Giles opened up the back.

“Out you come.”

He dragged Walker by the feet so his head hit the ground. Then he pulled him through the dirt. He knelt down, forcing Walker’s body against a tree. Walker became lucid for a moment. Fear, then anger, crossed his dark face. He swung his head at the kneeling Giles smacking him right under his fringe. Blood tracked down Giles face from the new cut. He kicked Walker in the guts. Walker went limp.

“Mate, what are you doing?” I asked, as Giles pulled the phone book out from under the driver’s seat.

“Teaching Mr Walker the consequences of striking an officer of the law.”

I felt my lip twitch with every thud of the phone book bruising internal organs and cracking ribs. There were no words or taunts, just his hands clasping and swinging that blunt instrument filled with the names, addresses, and numbers of Scarlet’s population.

I have dreamt of that moment many times. In those dreams I place my hands on Giles, and under the bright moon with the birds sleeping and the river flowing behind us, I shake out that malevolent spirit that had taken him.

The next morning, I went into the cold cell with its steel bed and tiny window letting in the morning light. Markus Walker lay there. I kicked his legs to rouse him but he didn’t stir. I shook his shoulders, he didn’t stir. I put a hand under his nose. He wasn’t breathing. I checked his arm for a pulse, there was none. I yelled out to Giles who ran in and double checked the pulse and breath.

We rang headquarters and told them there was a death in custody. They would send someone the next morning. We sat with the other two officers in the kitchen. Everyone found something to stare at on the floor. With the sound of dripping water around our mute lips, and knowing full well there was no life left in him, we felt the weighty presence of Walker next door.

It was mid-morning when Markus’s wife, Rose Walker, stood before us accompanied by her two sons—Oliver, a baby tucked into her chest, and Jimmy, a child of three, standing with his arms around her leg.

“Francis. I’d like to see my husband,” she asked, while patting the head of the toddler.

Giles rubbed his hands together, his face was wet with sweat, his fringe combed down covering the cut.

“There’s been an accident, Rose,” he said, through a thin voice. “You see, Markus…he was drunk, rowdy. He had a bad fall.”

I remember clearly how the baby grabbed at Giles’s hand as her knees buckled.

It was late afternoon when the mob of blackfellas rose like flood water out the front of the station. We boarded up and rang for guidance. Reinforcements wouldn’t be there for a couple of hours at the earliest. Bottles and rocks slammed and broke over the corrugated iron roof. We anxiously peeked through windows at the dark faces surrounding us. Smoke came in. They’d set the Leagues Club nearby on fire.

“Justice for Walker,” was yelled through the haze.

It wasn’t long before the front gates of the station were torn down.

We bolted along the back of the blazing Leagues Club and made it through the doors of the clinic a hundred meters away. The staff had already left. We secured the gates and waited, hoping nobody had seen us enter. I rang headquarters and gave an update.

Giles had a mad look in his eyes. He paced the waiting room while the other two coppers coughed and drank water in the kitchen.

“Let’s get out of here,” he said, his hand gripping my elbow.

Before I could reply, he’d pushed me through the clinic and out the back door.

Before I knew what was happening, we were running across bitumen and away from the burn, then over dirt and gravel and the smoke became more distant. On we ran further from the fury and fire towards that murky river and along its banks.

We ran until my legs ached and I could barely breath. When we finally stopped, the sun was setting above us through shredded clouds. Giles paced a circle on the river bank washing his face every now and then.

“I’m in trouble Mate,” he said, his face white and mad-looking in the moonlight.

“We both are.”

“In this together, hey.”

That’s when I saw the eyes shimmering in the moonlight down by the river. Hungry camp dogs were coming towards us scratching the bank for feed. Giles was so caught up in his thoughts, that it wasn’t till a dog was at his leg did he notice the pack forming around us. He kicked and it limped off. Another came and started to burr up. Giles pulled out his baton fending it off. I turned around and saw more eyes gleaming in the dark. I climbed a nearby gum and yelled for Giles to do the same. Instead, he started swinging. Dogs were yelping and snarling all around us. They inched closer to Giles as a group and pushed him to the river’s edge. His baton slipped and sank in the blackwater. A greyhound snapped at his ankle pulling him to the ground.

It was a staffy that got him.

It showed teeth and barked as it closed. It pounced at his face, its head a ball of muscle biting and tearing. Giles pulled up his arms. The staffy’s head shook from side to side. Giles howled, such a sound I couldn’t replicate. It was in his screams that I finally found the courage to act. I leapt down, pulled my gun, aimed at the sky, and discharged a round. The dogs scattered and I…and I saw what they did to his ear…

You, Akhurst, are the first person I have told this truth. This is where Arthur stopped and rubbed a finger across his nub for an ear.

“What happened to Giles?” I asked.

“There was a trial…”

I sipped my beer and waited for the rest of the story. The story I now remembered. The story of the death of my Uncle; my cousin Jimmy’s father. Arthur just sat there gazing into his half glass of beer rubbing his hands together.

“You must go on,” I pleaded, because for him to finish would mean that I would distil and reckon with a transference. Of course, the whole town had known about the trial and mourned the loss of justice. But how savage the detailed truth.

Staffy stared up at the ceiling and said something to God. His eyes welled with tears as he looked back down at me. “Don’t you see,” he said and pointed to his missing ear. “I am the man who lost that evening. I am the man who committed atrocities. I am Francis Giles.”

I left the pub quickly and walked towards my mother’s home. The crisp cool and fresh earthy smell of late afternoon accompanied me. Staffy knew it did not matter if I wrote or did not write his confession, bound by promise or not. I, the blackfella writer would be viewed as fabricator, conjurer, slighter, and the dredger of things long settled. Those dark words thrown against the pale page would be lost in the sheen of it. Truth in fiction, I thought to myself as I walked through the red rage of my new grief for the long departed. I shooed a couple of camp dogs as the dust came and stung my bare arms through a fresh gust of wind. I pondered the meaning of words. Arthur’s life would continue on despite his confession. His burden lifted and transferred onto me. Heavy it weighed as I inched closer to my mother. I approached the gate and smelt my welcome home dinner on the air, pork chops, apple sauce, and green beans. I thought of obligation. I thought, what of hope? Does hope not permeate through a certain telling of things? Words, words, words, words. The door opened and I embraced my mother on the land of my ancestors full of deep history. She wiped her tears and said that I was all grown up. I placed my heavy bag in a nook just past the door inside our home. She embraced me again and Arthur’s story was for a second time transferred. And I knew from that point on we would share the burden through our bond of blood and country.

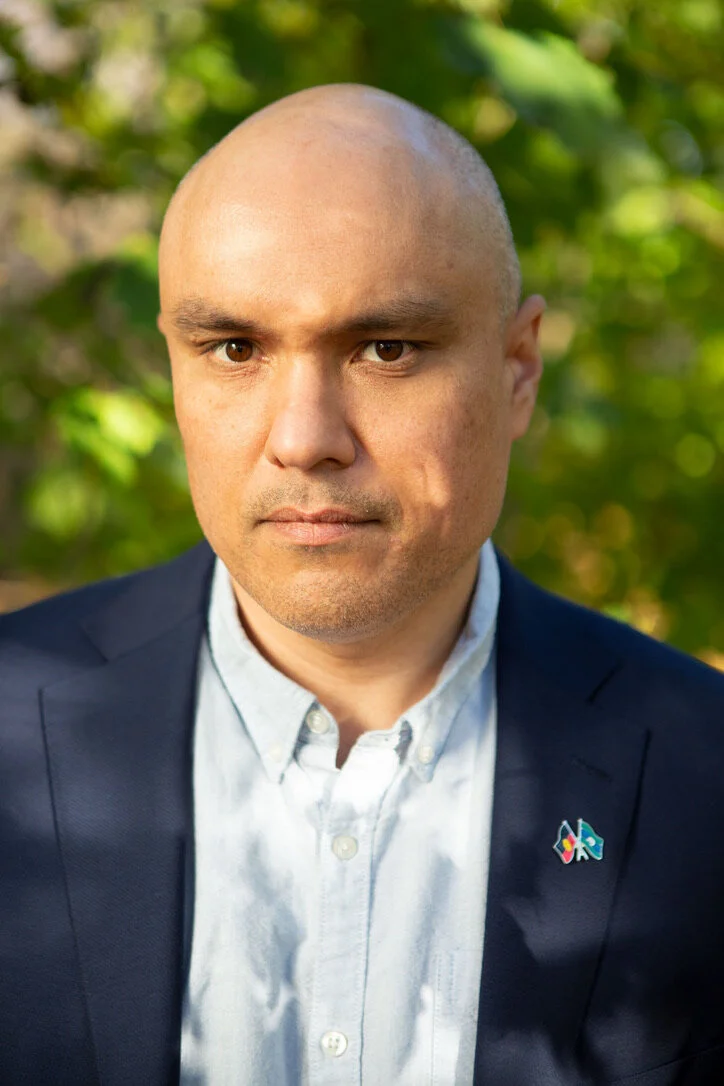

Graham Akhurst is an Aboriginal writer hailing from the Kokomini of Northern Queensland. He has been published widely in Australia and America for poetry, short fiction, and creative non-fiction. His debut novel Borderland will be released in 2022 with Hachette Australia. He is a Contributing Editor at Kweli Journal. He has an MFA from Hunter College, an Honours degree in creative writing and an Mphil in creative writing from the University of Queensland, where he was also an Associate Lecturer in Indigenous Studies. He currently lives in New York.

I would like to thank Wailwan writer, theatre-maker, and academic, Blayne Welsh for his considerate cultural edit of the manuscript.