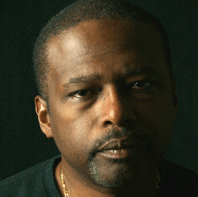

Kweli sat down for a dinner interview with Jeffery Renard Allen on March 2, 2011 at Cornelia Street Cafe.

LAURA PEGRAM: Thank you for sharing time with Kweli tonight.

JEFFERY RENARD ALLEN: It’s an honor to do this.

IVELISSE RODRIGUEZ: Can we talk about your novel in progress? You will be sharing an excerpt with Kweli.

JEFF: The novel is called Song of the Shank. It is very loosely based on a real person, a man named Thomas Greene Wiggins, a nineteenth century pianist and composer who performed under the stage name Blind Tom. Wiggins was born a slave in Columbus, Georgia in 1849, and he died in Hoboken, New Jersey in 1908. The novel is more or less set between the years of 1866 and 1868 in a large city, something like New York. Then there are flashbacks to various other times in Tom’s life, such as his childhood in the South. Although Tom is the novel’s central character, we see Tom mostly through the eyes of seven main characters—and a minor eighth—in third person. I present in detail their perceptions of him and what they want from and for him. I examine how he impacts their lives and how they impact him. Then in some of the novel’s final pages we get direct glimpses for the first time into Tom’s head and see the operations of his consciousness, as strange as it is.

LAURA: I can’t wait to read it.

JEFF: I can’t wait to finish it. (laughter) As I mentioned earlier, I am in the editing stage with this book. I did some edits in January; edits that might be the final edits. But I need to take another look at it. (Right now I’m too busy with teaching.) And I’m sure once I go back in I will find things I need to do to the manuscript. But I will hand over the book to my publisher by the end of the summer.

LAURA: You must have had gone through a period of extensive research for this project before you actually starting writing and reworking the language.

JEFF: Yes, I’ve been trying to figure out when I actually first began working on this book. I can’t quite pinpoint the time. Initially, sometime possibly in late 1998 and certainly by early 1999 I had come upon this idea of doing a novel that had three independent story lines. (This is an idea I have not completely abandoned. In fact, my next novel, Radar Country, will be another big and complicated one, a TransAtlantic story with four independent stories set at four different moments in time, including one in the near future.) Part of the inspiration for this formal experiment came from Caryl Philips’ multi-voiced novel The Nature of Blood, along with several of William Faulkner’s novels, like Light in August and The Hamlet –all narratives that have at least two independent stories. Initially the Blind Tom story was going to be a part of that book. Then in 2001—one day before the September 11th attacks—I started a fellowship at the Center for Scholars and Writers at The New York Public Library, where I began work on that book. Each fellow had to give a presentation to the group about our project. So I went into this elaborate explanation of mine, and one of the other fellows, the brilliant Mexican novelist Carmen Bullosa, said to me something like, “You know, cut the pretense. You should just write about Blind Tom.” Of course I thought, “Well, what does she know?” (laughter) It took me another two or three years to figure out that she was right. So somewhere around, I guess, 2004, I started working on the novel in its recent form, that is to say a book now solely focused on Blind Tom with the title Song of the Shank. I first tried to write a kind of novelized account of Tom’s entire life, starting from his birth in 1849 to his death in 1908. I planned an epilogue dramatizing Jack Johnson’s victory over Tommy Burns for the heavyweight boxing championship of the world— Johnson’s victory signaling the rise of a new era of vocalism and defiance in contrast to Tom’s seemingly passive acceptance of his fate, what scholars often call The New Negro. However, that draft didn’t work. I had written 500 pages and hadn’t gotten to the Civil War yet, a big problem. (laughter) Then I came up with another version of the novel where I started in 1865, not long after the Civil War ends, and then went both forward and backwards in time; the idea being that at a certain point, past and present would intersect and form a single story. That idea didn’t work either. Then, after a couple of months of mulling it over, I came upon the present version, which is based primarily on an alternative history. One of the premises of the novel is that during the 1863 draft riots in New York City, all of the Blacks in “the city” (Manhattan) were driven out of the city to an island off the coast of Manhattan, an island called Edgemere. So when the book opens, it is 1866, and Blind Tom is the only black person, as far as we know, who still remains in the city. A clandestine, he is under the care of Eliza Bethune, his former manager’s wife. (The manager was killed during the riots.) So that’s the premise. I began that version of the novel probably around 2006, I would say.

LAURA: We have to wait until January to read this? I actually want to hold a copy in my hands right now. It sounds wonderful!

JEFF: I wish I could work faster. But, I still haven’t answered your question really. Your question was more about research than story. I guess I kind of avoided talking about that. I did do a lot of research. (And there are still ten or twelve books that I plan to read about various subjects related to this project.) I would say from roughly 2001 through probably 2004, I spent a lot of time researching Tom’s life and, surprisingly, there wasn’t much that had been written about him in recent years. In his own time, he was really well known, a celebrity. He was widely reviewed in newspapers across the country and in Europe. Ulysses Grant wrote about him. Mark Twain wrote about him. Our very own James Monroe Trotter writes about him in his 1881 book Music and Some Highly Musical People: Remarkable Musicians of the Colored Race. He says that Tom is the greatest musician the world has ever seen. On the other hand, Willa Cather wrote an unfavorable review of him for her college newspaper. And later she used Tom as a partial basis for her character the Blind D’nault in what is probably her most celebrated novel, My Antonia. In a 1901 poem, an African-American poet wrote a poem called “Blind Tom, Singing.” (A shout out to noted UCLA scholar Richard Yarborough for bringing this poem to my attention.) By that time, Tom had been out of the public eye for a decade or more. He would return to the stage next in 1902 as part of a vaudeville company in Brooklyn. As I mentioned, Tom died in 1908, but in the early 1920s celebrated magician Harry Houdini wrote about him in a book. Already by that point, Tom had pretty much faded from memory, only about fifteen years after his death. I found a few scattered articles about him published from the late 1960s on. Tragically, this boy and man, who had been so highly praised and rewarded—well, his handlers got all the money—for his musical talents in his own time had been more or less erased from musical history. Eileen Southern, in her seminal 1970 text The Music of Black Americans, offers the only serious examination of him as a musician that I could find. One study by a New York Times music reviewer goes so far as to mock Tom as a pianist and performer and considers him unworthy of study.

This silence that surrounds Tom is particularly striking when you consider that he was one of the most well-known and commercially successful pianists of his time. He was contemporaries with Liszt, Anton Rubinstein, and Louis Gottschalk. A white man from New Orleans, Gottschalk was the first American to become internationally famous as a pianist and composer in the 1840s. Blind Tom might have been second or third, but one way or the other he was also a pioneer much like Frank Johnson, an African-American musician—bugle and violin—and bandleader from Philadelphia, who became our country’s first full time bandleader in 1818. He was also the first African-American to publish his compositions as sheet music and was the first to lead American musicians on a visit to Europe, including African Americans. Not only was he a highly respected instructor, he made several important contributions to European classical music. I would think that Tom’s contributions were also significant, given that he had a number of compositions that imitated the sound of natural and man-made phenomenon, like rainstorms and sewing machines, even as his stage recitals deviated in significant ways from the formal models. He would invite members of the audience to play original compositions, which he would play back and improvise on. And he gave oratory in several different languages and performed other feats of memory. (I had quite a bit of fun with all of this stuff in the novel.) So Tom was a force to be reckoned with in his day.

However, today when you research his life, you find that most of the people who are interested in him are psychiatrists or other kinds of medical professionals. Their interest is due to this whole phenomenon of the savant, the autistic savant, because that is how Blind Tom is usually characterized. At first I was finding that there would be a chapter here and there about him in some sort of medical tome written for the general public. Then I discovered that there was a prominent African-American musicologist, Geneva Southall, who taught at the University of Minnesota and who devoted the last twenty years of her life to researching Wiggins. She published a three-volume biography about him between 1979 and 1999. But I found that only the third and last volume was readily available. The first two volumes had been published by local Minnesota presses that no longer existed, and I couldn’t find copies of those books anywhere, no matter how hard I tried.

LAURA: You couldn’t find them at the Schomburg Center?

JEFF: No. Eventually I did find them, almost by accident, at the University of Minnesota library. This library might contain the only copies of those books that remain anywhere in the world, besides the Xerox copies I made of them. Indeed, I discovered a lot of valuable information in those two books, all three books really. About two years ago during the centennial of Tom’s death, a British woman published a biography about him, a book I plan to read this summer. In any case, I did a tremendous amount of research about Tom’s life and also about a host of other topics. Because Tom was primarily a classical musician—he was not a folk musician—who had a classical stage repertoire, I needed to learn more about classical piano and European classical music as a whole. I also read up on the lengthy and varied historical period between Tom’s birth and his death. Ultimately, most of this research didn’t figure into the book in any way, but you know, that’s how it goes, I guess.

LAURA: I would think that you also did quite a bit of listening along with the reading. And what kind of preparations did you make to write about a musician, beyond reading up on Tom and classical music?

JEFF: Indeed, I did do a lot of listening. Let me come back to that. First, let me say that it is extremely hard to write well about music. Just look at the average music review in a magazine or newspaper. How easy it is to fall into the usual clichés. I certainly went back and had a look at some novels that have handled music skillfully, including Marcel Proust’s Swann’s Way—Proust is hands down one of my favorite novelists; his language, his ideas, his representation of consciousness might be unmatched; John A. Williams’ Night Sky—Williams, now that is an African-American novelist who has kind of been forgotten, who hasn’t gotten the attention he deserves; Thomas Mann’s Dr. Faustus; Thomas Bernhard’s The Loser; and Michael Ondaatje’s Coming into Slaughter. Then there are a number of nonfiction works that remain in my memory—a writer’s recall—things like poet’s David Henderson’s biography of Jimi Hendrix, which I first read when I was sixteen or seventeen, a defining book for me as a writer; Henderson’s use of language, his way of inhabiting Jimi’s body and mind. Amazing stuff. And Miles Davis’ autobiography, which has also been crucial to my development as a writer and artist; Amiri Baraka’s two celebrated books Blues People and Black Music; A.B. Spellman’s Four Lives in the Bebop Business; and Fredrich Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy: Out of the Spirit of Music, a book that my good friend and writer Randolyn Zinn suggested I read. Then the essays of Greg Tate and Stanley Crouch often have excellent renderings of music. And that is the challenge really, how to translate sound into language, into words.

LAURA: How did you first learn about Blind Tom?

JEFF: I first discovered his story in one of Oliver Sacks’ books that I was reading for pleasure back in early 1998, if memory serves me correctly.

LAURA: I love Oliver Sacks. I am reading Musicophilia now.

JEFF: Yes, Musicophilia. That book is wonderful, as are all of his books, I think. But Sacks actually writes very little about Blind Tom in that book, a paragraph maybe, or only a footnote to a paragraph if I’m not wrong. But in his book An Anthropologist on Mars, for the purpose of historical comparison, he writes about Tom for a few pages at the beginning of a chapter about “another” savant—I use the word reservedly—an Afro-British kid who can sketch or draw an imitation of anything he sees. I was intrigued by this story of a Black musical celebrity from the nineteenth century that I had never heard of, and also by Sack’s description of Tom’s stage performance. Among other things, he could play three songs at once in different keys: one song with his left hand in one key, a song with his right hand in another key, and he would sing a third song in a third key. I said to myself, “What is this?” I started to do a bit of research about him and eventually decided that I wanted to really write about this guy as a fictional character in a novel. But even after I did all of that research, read the three biographies and everything, Blind Tom was still a mystery to me. I had no idea what made him tick. For Dr. Oliver Sacks, Wiggins was that rare being, an autistic savant—there have been only about 100 documented cases of savants since the term was first invented in the nineteenth century—and for that reason, Sacks doesn’t believe that he was truly creative, only an imitator. At the other extreme, Tom’s biographer, musicologist Geneva Southall believed that Tom was a true musical genius, but that his stage manager fabricated this whole image of the idiot savant as a way to sell concert tickets. So they built on the commercial attraction of his blindness—as far as I can tell, Wiggins was the first musician to use the moniker “blind” as part of his stage name, like the many blues singers who would do so in the twentieth century, or the gospel group The Five Blind Boys of Alabama—and added to it this myth that he was an idiot and that he had no musical training and was incapable of such training. Then, of course, he was Black in the era when most white people thought we were incapable of intelligent thinking—in Tom’s case, the intelligence required to master and perform classical music. But the fascinating thing I found was that during all this no one really talked much to Tom himself about his feelings. There were no interviews with him, only a few brief statements attributed to him that he had given here and there to journalists. That absence ended up working to my advantage because my imagination began to create what I didn’t and couldn’t know, what I didn’t and couldn’t see. This process proved true for several characters in the novel who are based on actual people that were affiliated with Tom.

LAURA: And what kinds of things did you listen to? Did Blind Tom make any recordings?

JEFF: Tom died pretty much before the recording era began, although he certainly was around when the piano rolls went into mass production in the late 1890s. However, he wrote and published over five hundred compositions, which have yet to be properly catalogued and collected. Geneva Southall recorded some of them back in the 1980s or 1990s that exist on a CD at the University of Minnesota library. Then in 2000, a white, Brooklyn pianist named John Davis did the first commercial recording of some Blind Tom compositions. I own copies of both the Southall and Davis recordings, but I deliberately avoided listening to them as I was writing the novel, since I didn’t want these recordings to inform or color the sound of Tom’s music that I had already developed in my imagination. Instead, I listened to dozens of recordings of classical pianists, listening to how they interpreted some of the compositions by Bach, Chopin, Mozart, Liszt, Beethoven, and other composers that Tom regularly played, and listened to the whole corpus of classical piano composition as best I could.

LAURA: And what are you reading now?

JEFF: I just finished re-reading Dexter Palmer’s novel The Dream of Perpetual Motion since I am hosting him at The New School this week. Also re-reading the works of two other writers I will be hosting this semester, Tiphanie Yanique and Heidi Durrow. All three writers have just published their first books. I’m too busy with teaching to be reading other stuff. However, this summer I have a stack of about fifteen books I plan to look at in whole or part that I feel might be useful when I go back to the novel and begin my final read through and edits, everything from the most recent biography of Blind Tom that came out about three years ago, to a book about the origins of the Black Panther Party, to William Melvin Kelley’s novel A Drop of Patience, which has a blind protagonist, to a memoir by a blind Indian man, to some novels and other books about free black people living in New York and other northern states during the time of slavery, to some books about slavery itself—a few slave narratives, Margaret Walker’s novel Jubilee, and David Bradley’s once celebrated but now underappreciated novel The Chaneysville Incident, one of the most significant works of literary fiction in our country’s literary canon.

IVELISSE: How long did it take you to write your first novel, Rails under My Back?

JEFF: It probably took about 6 or 7 years.

IVELISSE: I was thinking that 10 years is about right.

JEFF: Yes. I started the novel at the end of 1990. In fact, I came to New York from Chicago in December of that year to meet with an agent about representing me. I was still in graduate school working on my PhD and only writing stories (and poetry and some critical stuff) at the time. She liked my stories, but told me that she needed a novel, and I said something like, “I’ve already started a novel and will be done with it in six months.” So we signed a contract for her to represent this novel for a period of one-year. I made up the novel’s title on the spot, taking the title of a poem I’d written that a friend had said would make a good book title. The title of that poem had actually come to me in a dream. In any case, although I signed this contract, I had only been thinking a little bit about a novel in the previous months, a process that was pretty tentative. I had written no actual pages or even thought the basic story through. Then on the flight back to Chicago, I wrote the novel’s opening paragraph pretty much word for word as published. However, I didn’t start working on the book in earnest until I finished graduate school in 1992, and didn’t complete the first draft, or most of a first draft, until late 1994. At that point, my agent began to show it to editors. And the responses I received from editors confirmed something that I had already been thinking, that the book’s overall structure was faulty. So I spent about three years simply revising the structure. My agent read the completed manuscript in 1997 and thought that the opening chapter was too complicated and had to do more to establish road signs that would help guide the reader through the book, a map for reading. So I spent six months revising the opening chapter. That’s pretty much how it went. Started the book in 1990 but didn’t finish it until early 1998. And that agent I met in 1990 is still my agent today.

LAURA: Do you have a group of writers that you share your works-in-progress with?

JEFF: I’ve had that in the past. I often used to send stuff to my novelist friend Steven Varni, and would share things with another writer friend, Josip Novakovich, and sometimes with my mentor and close friend Lore Segal, the novelist and teacher who introduced me to my agent many years ago. And other friends too whose reading instincts I trust. But now I am just working with my editor on Song of the Shank.

LAURA: It’s good to have an editor that you trust.

JEFF: Or at least that you trust sometimes. (laughter) No, he’s actually extremely good, extremely sharp.

IVELISSE: Is it ultimately about having the same vision for your book with an editor?

JEFF: Yeah, I think you want somebody who understands what you are trying to do and where the manuscript needs to go, someone who can help you reach what you are trying to achieve, what you are striving after, and not someone who will simply force you to do edits to make the book shorter or to possibly make it more marketable or to meet whatever agenda they have.

LAURA: Can you speak about how the role of an editor has changed over the years?

JEFF: What I have heard by talking to people in the industry over the last several years—writers, editors, publishers and publicity people, and agents—is that the role of the editor has changed significantly even from how it was in 1998 when Elisabeth Sifton took my novel for Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. Already by then few editors at the major New York houses still performed any major hands-on editing. (Elisabeth was one of those few.) Editors were far more involved than ever before in the business side of publishing, the packaging and marketing aspects of it. That’s still true today, only more so. Now, it is also rare for any single editor to make the decision alone that “I will buy this book.” Such decisions have become a roundtable process, a corporate decision that involves all of the editors in the house and the marketing staff.

LAURA: Yes, the industry has changed dramatically over the past 10 years.

JEFF: And it is only getting worse for literary fiction. That’s very encouraging. (laughter)

IVELISSE: I’m going to quit my job right now. (laughter)

JEFF: I used to give my MFA students a doomsday speech about publishing just to make them aware of the harsh realities. But I have more or less stopped doing that.

LAURA: So do you give them a watered down version of it now?

JEFF: For a time I just tried not to talk about it at all. Then I realized that my silence was doing a disservice to my students. So now I really stress that if they are serious about getting published, they have to work really hard to find people that will help them, they need contacts who can introduce them to agents or recommend places (magazines and journals) where they should send their work, contacts who are willing to write a letter of recommendation for a grant or a residency, that kind of thing. Students also need to know that in today’s climate, book publishers don’t simply accept a manuscript based on its literary merit. They think as much about the writer of that book, want to know that the writer will be actively involved in marketing that book both before and after it comes out. Back in the day, marketing was the house’s responsibility. Now it’s a partnership.

LAURA: I see.

JEFF: I must say, I find much of this distasteful, disgusting even. I am a fairly private guy, shy even, at least for much of my life—being in the public eye as both an author and an educator has changed me, and I have never been into self-promotion, although I do enjoy giving readings. I think that the steady erosion of book culture in our country continually places these artificial and often arbitrary demands on the writer. You know ten years ago if you wanted to publish a collection of stories with a major house you had to do a two-book deal for a collection and a novel. But not everybody is a novelist. Those kinds of deals have dried up, so it’s even harder now to publish a story collection. For reasons never made clear to me, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux had no interest in publishing my book of stories, Holding Pattern (2008)—well, when I presented it to them more than a decade ago and after the title and contents were different—so what was I to do? And those writers out there who are primarily story writers, what are they supposed to do? Word has trickled down somehow because I see more and more students submitting novel excerpts in my workshops and less submitting stories, where before, from the time of its inception in our country, the workshop model was centered on the short story. I’m glad that I still get a good balance of the two forms, that young writers have not abandoned the short story form altogether. (Of course, there are still fortunately hundreds of journals in our country where one can still publish short fiction.)

LAURA: That is interesting. I’m glad you are saying this because I wanted you to speak some about teaching.

JEFF: I do enjoy teaching, although admittedly it can cut significantly into your writing and reading time, and your thinking time too, and to some degree, the meditative space that all writers need. Some authors hate workshops and refuse to teach them. (I won’t name any names.) They will only teach literature courses. Quite a few people think that MFA programs are a big hustle, because, first, you can’t teach writing, and second, most people who graduate from an MFA program will never publish a book—so the average MFA program does little in the way of helping a student writer become an author. To take this last point, I don’t know the exact numbers, but, indeed, it is fair to say that less than 10% of people who graduate from an MFA program will publish at least one book someday. (The numbers are probably even lower.) The numbers are a matter of concern when you recognize that nationwide about three thousand students a year graduate from the many MFA programs out there. (The numbers of programs keep growing.) Here is what most concerns me:

I find that most students who graduate from an MFA program stop writing altogether after a few years. Some encounter the realities of the publishing industry, the high level of competition involved in getting a story in a magazine where 700 other people, many also MFA students and graduates are also submitting at the same time in a given month, not to mention those who’ve already published. The competition involved in getting an agent where some agent who doesn’t know you from Adam reads your query letter along with the other 150 she receives that day. These students, no matter how talented, face that, and many of them get discouraged and stop writing. Others take full time jobs and eventually stop writing, or they simply lose interest because they are no longer actively involved in a community of writers. (If nothing else, a writing program, undergraduate or graduate, should be a community.) Then too, I suspect, some simply don’t have the discipline it takes to create and sustain a career in this profession. Talent is not enough. Isn’t that why athletes train? A writer doesn’t necessarily have to write every day, but she or he has to read and think writing, and then has to be willing to put in the hours every day when the time comes. How many people can do that? And how many people can do that for years at a time, the years required to write, revise, revise again, and edit a novel, or maybe a collection of inter-related stories or some sort of book-length poem. (I really believe that writing a good novel is the hardest thing one can do in life.) As I said before, I have been working on Song of the Shank–and one or two other novel projects that I plan to come back to—since 1998, and worked on Rails under My Back from 1990 to 1998, finish one novel and start another. That takes a certain type of discipline that is tough on both mind and body, and that can have detrimental consequences for those closest to you, a significant other, your family and friends. In an interview on 60 Minutes many years ago Ed Bradley—I think it was him—asked Miles Davis what it was like to be a musician. And Miles said something that has stuck with me because it is honest and true. Miles said, “Music is ninety percent of my life. My wife and friends are the other ten percent.” That is how an artist thinks, how s/he moves in the world, how s/he is in the world, and what it means to be an artist. Then there is the difficult process of actual creation, of making. And the third step is mastery, craft.

Many people can write and be good at it, but few can be a writer. An MFA program can make you a better editor of your work, (workshops are ultimately about that, learning to become a conscious editor), can teach you certain techniques through literature classes, workshops, and seminars, can tell you much about the life of the writer, and may even provide you with valuable contacts, but it can not make a non-writer into a writer, turn a laymen into an artist. This is not to say that the process of imagination and creation is limited to only a privileged few. Only that a few, artists, have a special relationship with this process, a special understanding of it, and a willingness to engage with it. (We should encourage everyone in our society to be creative, to read, imagine, and think critically, and to create and express in one form or another, be it becoming an active member in a book club, or having a serious and regular engagement with a sport or some form of physical competition or challenge, or starting a non-profit or NGO, or attending good plays, films, or other performances, or listening to good music and pondering over it or dancing to it, or pondering as you dance. The possibilities are many.)

An artist knows that s/he is an artist. A writer knows that s/he is a writer. This is something I knew from the time I was eight years old even if I could not articulate it as such, even if I knew absolutely nothing about publishing or any of that. Through hard work and with some level of training—even if it’s only reading—certain individuals are capable of writing a decent or even good book. But a true writer will always try to elevate the work to that next level where few can reach. So that is an important place to begin, with that understanding. If you are a writer, write. If you are not, do something else. Simple. (Here is one great possibility for our MFA programs nationwide: at the least, they are creating a generation of serious readers, no small matter, for readers are thinkers. No one can take that away, the serious engagement with thinking that is so absent today in our vulgar and plastic culture of commerce and greed—what DuBois calls in The Souls of Black Folk “the dusty desert of dollars”— warmongering and jingoism, reality TV, reality-less cinema and visual proliferation, and cult of personality, a culture that both celebrates artificial talent and creates artificial celebrities. At least that is my hope.) In the end, writing is an act of faith. Believe that if the work is deserving it will find its way into the world and find an audience, no matter how small. Otherwise why do it? But writing I think is much harder than being a musician or a visual artist, even an athlete. The writing is hard enough, those hours and days you have to spend on a paragraph or scene, in figuring out how to get a character into a room and into a chair. It is very tough to stay self-motivated no matter how talented you are. And once the work is done, you have to go face first into the maelstrom that is the publishing industry.

LAURA: There is a quote that I only half-way recall from your interview with John Edgar Wideman. He said something about “the hustle.”

JEFF: Yeah, he did in fact say that. I first met John in 1989 when he came to Chicago’s Southside to give a reading from his book of stories Fever—it had just come out—at Haki Madhubuti’s bookstore on Cottage Grove not too far from where I had grown up in Chicago. (Haki, the founder of Third World Press.) At the time, I was still in graduate school at The University of Illinois at Chicago, working on my Ph.D. When I brought my book up to John to be signed, I told him that I was a writer and told him how much I admired his work. (I had been reading him for about five years at that point.) So he signed it, “Writing is a tough hustle, but well worth the effort.” I later quoted the line in my essay about John in Poets & Writers.

IVELISSE: It’s interesting that you say students must find someone that can help them. Do you really think that students should not send out blind submissions?

JEFF: Yes, because many simply don’t know any better. As far as I can tell about 80% of what we learn about writing comes from reading. Workshops and such make up the other 20%. Then learning about the whole process of getting published requires study too simply because of the nature of publishing in America. It is just so competitive. It is hard to gain the attention of an agent. So what I do is this: when I have a student who I am trying to help find an agent, I give them a specialized list with the name of my agent and the names of agents who represent some of my friends, and tell them to make sure to use the name when they send out the query or cover letter. Ideal if I could personally introduce that student to every agent on the list, but that simply isn’t possible. By doing things blind, you probably won’t get very far.

LAURA: Contacts . . .

JEFF: Yes, contacts. I encourage my students to go to writers conferences—whether it be Bread Loaf, Sewanee, Summer Literary Seminars, or VONA—to try and meet as many writing professionals as possible, authors, agents, publishers, in the hope of getting them interested in your work and trying to support it. That’s the reality of this publishing game. I would go so far as to say that I don’t think that anything in this business is completely objective, including the awarding of residences, grants, and prizes. Much comes down to who the judges are at any time. I am probably sounding like a downer about awards.

LAURA: No, . . . it’s truthful. But people are encouraged by the small presses, . . . particularly with the recent success of Tinkers.

JEFF: Yes, we should look at some of the good things happening out there. For example, I think that in terms of African-American writing, it’s a very exciting time. You look at all the poets who are publishing and there is such a wide variety of stuff, such a wide range of topics and aesthetic choices. For whatever reason, the younger generation of African- American fiction writers are not producing work that is as varied or exciting. I think that Edward Jones’ novel The Known World is the most significant work of fiction produced by an African-American writer since John Wideman’s novel The Cattle Killing came out back in the 1990s. I also admire Colson Whitehead’s John Henry Days for quite different reasons, although in many ways it is a tour de force, a formal and intellectual exercise with nothing of the truth and power of the Jones novel. By and large, I would prefer to read the latest book by John Wideman, or Percival Everett, or Paule Marshall—she, seems to have stopped writing fiction—or even Toni Morrison—although the quality of her work has declined significantly since Jazz, you can always find something of interest—rather than follow some of the young fiction writers of today. I do, however, follow some writers I like quite a bit, namely Whitehead, Victor Lavalle, Paul Beatty, and two of my closes friends, Calvin Baker and Bayou Ojikutu. And other folks—Edwidge Danticat, John Keene, Danzy Senna, Nelly Rosario, Eisa Ulen, and Tayari Jones —have produced books I admire. I have to watch what I say since these people are all friends, even if I don’t see or correspond with them as much as I would like.

LAURA: Tayari Jones is coming out with a new title next month. And Mat Johnson is actually reading tomorrow night at McNally Jackson Books.

JEFF: I first met Mat Johnson back in 2004 when we were both teaching for the Hurston/Wright Foundation on the Howard University campus in Washington. He had just started Pym, the novel just published that is his response to a racist Edgar Allen Poe story. Mat is an important writer and teacher. And I essentially met Tayari Jones also through the Hurston/Wright Foundation—this says something about the importance of literary organizations—when I was asked to be a judge for one of their prizes, a prize that Tayari easily won for her first novel, Leaving Atlanta, which is based on the Atlanta child murders. Tayari was a child in Atlanta at the same. One of the sad facts she reveals in the novel is that our society views black children as worthless. That is a truly profound metaphor because, by extension, it implies that our society thinks that all black people are worthless. Some would say that this is an outrageous, although it is proven, fact. Allow me one example.

IVELISSE: Please.

JEFF: I recall one weekend in Chicago three years ago—before Obama was elected—when twenty-seven black and Latino men where shot in a single weekend.

IVELISSE: Wow.

JEFF: And just last summer with Obama now as our president almost triple that number, from what I’ve heard, of black and Latino men shot. Now what did those in authority, what did those in the know, say, do in response? Nothing as far as I can tell. Even more striking since President Obama made his bones in Chicago. I can guarantee you that national outrage would follow the shooting of twenty-five white people in a single weekend in Chicago or New York or any other American city.

IVELISSE: Indeed.

JEFF: The ugly workings of race are institutional, cultural, systematic, and pervasive. And we, every one of us in the country regardless of skin color, are affected by it in one-way or another. (You can’t both live in a country and be outside the country at the same time, just as one can’t swim without getting wet. And we, all of us in this country, get wet when it comes to race.) But we should get back to the subject of fiction.

IVELISSE: Yes, we should. But what you’ve said is much food for thought.

JEFF: I hope it tastes good. (laughter) I also want to say that the young (or present) generation of African fiction writers is starting to produce work of major, international significance. I would say the same for some writers in Canada, the U.K., Europe, the Caribbean, and Latin America, but to a far lesser degree since the largest body of work from black writers outside the United States is coming from the continent. Kojo Laing, Esi Edguyen, Abdulrazak Gurnah, Alain Manbanckou, Emanuel Dongala, Zakes Mda, Moses Isegawa, Aminatta Forna, Zukwisa Warner, Petina Gappah, Niq Mhlongo, Mohammed Naseehu Ali, Doreen Baingana, and the late Yvonne Vera. And especially the Nigerians: Chris Abani, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Helen Oyemmi, Sefi Atta, Helon Habila, Chika Unigwe, Elechi Amadi, Igoni Barrett, Teju Cole, and Ben Okri, of course, to name a few. And some of the older generation of writers is still producing important work, namely Ama Ata Aidoo, Nuruddin Farah, and Ngugi wa’Thiongo. In some ways, the work of this younger generation might be fresher in themes and situations, and for those reasons be of greater importance than what the younger generation of fiction writers is producing over here in the United States. However, although this work is even brilliant at times, I strongly feel that the African novelist and short story writer, for the most part, has not fully broken with outmoded western forms and genres to fully take up the challenge of formal innovation as a necessary stage of personal and national expression. African-American vernacular idioms—the spirituals and gospel, the blues, jazz, speech, folktales, quilts, etc.—provided black American writers with formal models that can and have been extended into innovation directions in fiction. This call for and attention to a “black aesthetic” was possibly the most lasting contribution of the Black Arts Movement of the mid to late 1960s and early 1970s. And you can see such an aesthetic at work in writers that pre-date the Movement: Charles Chestnutt in The Conjure Woman and Other Stories, Jean Toomer in Cane, Richard Wright’s stories in Uncle Tom’s Children, much of Zora Neale Hurston’s fiction (and nonfiction, for that matter), Ellison in Invisible Man, and James Baldwin in Go Tell It on the Mountain and some of his other novels and stories, and even in the work of certain white writers, some of Herman Melville’s stuff, Mark Twain (The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn), Dubose Heyward (Porgy and Bess), and William Faulkner, the greatest novelist America has ever produced. So I’m still waiting to see what will come out of Africa in terms of the African writer’s articulation of a distinctive aesthetic. Said aesthetic will have a profound impact on literary fiction, far beyond anything we’ve seen so far. As well, I don’t feel that African writers, for whatever reason, are having the same impact on verse that African-American poets are. African, Caribbean, and African-American literature are all still young when you think about this question of self-definition through formal innovation. We African-Americans have been at it the longest, for better or worse, about 250 years.

IVELISSE: I didn’t get to read the article, but I remember looking at The New York Times, it must have been yesterday, and the caption was about a book proclaiming the end of African-American literature, a book called What Was African-American Literature?. What are your thoughts about that? Also, you just said that this is an exciting time for African-American writers. I read Tayari Jones’ blog and sometimes see posting where people say pessimistically that you need to write street lit in order to get published.

JEFF: I think I understand what you asking. As African writers we exist between these two extremes. On one hand, we live in this supposed “post-racial” area now that Obama is our first Black president. So this book you mention by Kenneth Warren—and Toure’ had an article out recently that made similar claims…I think writers who make these claims look at it all too simplistically. To start, we know that race is a myth, a social construction. Recent studies in DNA have shown that the human race is one species and that everyone in the world today, regardless of skin color, descend from a group of Bushmen in South Africa 100,000 years ago. You can go back to something like Charles Darwin’s 1874 book The Descent of Man and see that perceptive scientists, even back then, recognized the falsity of this idea of race and separate races. This, however, does not change the fact that we live in a racist country, that black people in this country face systemic discrimination, abuse, and oppression. Only now, we cannot really have that conversation any more because of this post-racial era we are supposedly in. And to suggest that the black writer has achieved parity with his white (male) counterpart is simply asinine. What universities have they been teaching at? What publishing houses do they know? And it’s probably far worse for Latino and Asian-American writers. I defend any writer’s ability to write about any subject s/he chooses, as long as that writer writes honestly and well. People like Warren and Toure’ operate under a racist assumption that only proves how pervasive racism still is in our country: one cannot be “black” and also be universal, to write about “black” subjects is to fall into the simplistic and uninteresting traps of identity politics. So we must be something other than black to be cosmopolitan. You know, back in the late eighties Trey Ellis published an essay called “The New Black Aesthetic” in Callaloo where he showed how the young, post-Civil Rights and Black Power generation of writers emerging in the eighties were what he called “cultural mulattoes,” writers and other artists who were shaped by and borrowed from many ethnic practices and idioms. Ellis’ argument, at least, has some real intellectual substance, weight, but even he was faulty in his thinking. Haven’t we always been cultural mulattoes to one degree or another? So many reviewers and literary scholars out there seem to believe that black writers only read other black writers and only influence other black writers. How stupid is this?

The other extreme has to do with just that kind of literary ghettoization. Some would have us be black in an almost stereotypical way and turn out these trashy so-called “urban” or “street lit” novels. I think those books have no value, absolutely none. I don’t buy that argument that reading anything is better than reading nothing. I think it was Hemingway who said, “Crap in, crap out.” I couldn’t agree more. We are asked to celebrate the buffoonery of a Tyler Perry because he is a black entrepreneur with his own movie studio. Art at its best is always engaged with three processes: vision, voice, and value. Mastery over a given text is about learning to recognize what you feel about the world—that can be a process of discovery during the actual writing itself, as opposed to something thought out in advance—and learning how to then articulate that vision on the page, and finally understanding that what you express is inevitably in dialogue with what has come before, what is out there now, and what will come after—essentially, all those texts that you deem valuable, worth reading, worth returning to. So rather than be some hack writer or filmmaker, I would rather stop making art altogether, give up this life of the artist. Crap in, crap out.

African or African-American—what’s so encouraging is that there are a lot of good young writers out there who are producing some really solid books, and some groundbreaking books in some instances. That’s going to continue one way or the other. I fear, however, that literary fiction may go the way of poetry in recent years. A new author will need to win a book contest in order to publish his first and second books. If this happens, it will most likely happen first with short fiction, story collections.

IVELISSE: You say it’s an exciting time, but what are you comparing that to? The past 10 years?

JEFF: Let’s say within the last ten or fifteen years. Neither the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s nor the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s produced as many writers as we have both writing and publishing today, not to mention the variety of work. There are more people now to try and keep up with than ever before in the past. I just can’t keep up with everyone who is publishing books. And what I do read is only the tip of the iceberg. That is what is exciting. As I mentioned before, I am reading this guy Dexter Palmer. He’s an African-American writer, but he doesn’t deal with race at all. Now, is that a good thing or a bad thing? I don’t know. You decide. Plenty writers still address the complexities of race—despite Toure’s objections—and the many other complexities of life. Just the fact that Palmer is able to do that and find a publisher says something.

IVELISSE: Your book Holding Pattern isn’t really a book about race either. Was that a conscious decision?

JEFF: I think all of my fiction is about race because I write about black people, that simple. I mean, if my fiction is about race at all—once again, I use the word race “guardedly” for fear of playing into this construct that has done so much damage in our country and the world and continues to lame and maim—it’s really about the cultures that I knew growing up in Chicago and in various parts of the South, from West Memphis, Arkansas to towns in Mississippi. I don’t know what I want to say about that. I mean significant portions of Song of the Shank are rendered through the eyes of white characters. Is that an issue of race or simply a matter—technique?—of empathy, a writer’s ability to put himself into the shoes of another person? And this book will obviously examine questions of race differently from Holding Pattern or even Rails under My Back because it is set in a time where everything was about race, during slavery and the immediate post-Civil War years.

IVELISSE: But not every book has to be about race. I remember Sandra Maria Esteves came to UIC, and she came to my professor’s class, and we read some of her poems and it was really about being human. Her old school poems were about race. I think the normal trajectory would be to write about race first and then move on to other things. But that’s not your trajectory. You seem to be doing the reverse. Or maybe you are weaving in and out.

JEFF: Well, I feel that serious thinking about race is important, for a number of reasons, but not necessarily the most obvious ones. To go back to something I said before, I think I have read at least six books about the scientific debunking of the notion of race through DNA research. So I know that race is this false construction, but how do I put that knowledge to use in the world? The question is this, “Do I define myself as an African-American writer, a black writer?” a question I myself have asked many writers that I have interviewed over the years, including several writers whose work I admire: John Edgar Wideman (of course), David Bradley, who was one of Wideman’s students at the University of Pennsylvania, and Edward Jones. (Jones responded, “Yes, I am a black writer. That’s who I am.”) That would also be my first response. But this is a multi-faceted question. If you will allow me.

IVELISSE: Of course.

JEFF: I have heard John (Wideman) point out that Richard Wright wrote an essay about this question of the black writer’s moving beyond race back in the 1950s. And we should note that both Wright and Zora Neale Hurston each published a novel where all of the central characters were white, Wright’s The Outsider and Hurston’s Seraph on the Sewanee. Percival Everett has pointed out that we as readers automatically assume that a character in a novel is white unless the author uses some explicit adjective to identify a character’s skin color. Why must this be, why do we make this assumption? If we had more time we could look extensively at the pervasive hegemony of racist ideas and assumptions in American culture and society today. So my question is this, who most benefits in our new post-racial America, who benefits from this idea (ideal) that is not an actuality? (Great if it were true.)

So, no, I don’t buy into any of this discourse about a post-racial America or post-racial literature, or the end of African-American literature, and I am even suspect about most of the emerging discourse around this notion of “bi-racialism” because it often seems like a slippery way to both avoid blackness and dismiss and reject it as something other and less, and also caters to our country’s fascination with the supposedly exotic.

IVELISSE: What are the topics and themes that most interest you?

JEFF: I am very much interested in the whole question of family. This issue has carried through the two books I’ve published as well as the novel I am presently working on. And I am interested in the question of place. So if I write about Chicago, even if I call the city by another name, how can I write about that place where I grew up, one of the most segregated cities in the world, without examining how the ugly facts of race affect people there? I can’t consider my feelings about the city without considering how race has played into it. I grew up in a segregated city and come from people who grew up in the segregated South, and I now live in a heavily segregated city, New York. With Obama’s election, there are now so very few questions posed about race, as if we have somehow reached racial parity in a country where black people are shot down in the streets of Chicago and Brooklyn and Los Angeles and Philadelphia and West Memphis and Washington and Baltimore—many such towns and cities—on a daily basis. Where the prisons are full of black men. Where the majority of black children live in poverty. Where most black children receive a poor education. I can go on and on. That’s a conversation we should be having, so why aren’t we? Did I answer that right?

IVELISSE: Any answer is the right answer.

LAURA: You talk about your interest in family and your work. There is an article you did in Poets & Writers where you specifically referenced your Aunt Beulah. How did she contribute towards helping you to develop your craft? In the article, you made a comparison between Wideman’s aunt, who helped him develop as an artist, and yours.

JEFF: I think in that article I was talking about when Wideman had shifts in his career, although he might view the whole matter differently. I don’t know. His early books were much different from the ones he started to publish in the eighties and later. And then his voice became very different, too, I think. In many of his works of fiction he started talking about his Aunt May, who was the family storyteller. It wasn’t quite the same with me. My Aunt Beulah was more or less the family storyteller, but she wasn’t necessarily a great storyteller. You see, she was the only one in the family who wanted to talk about things that no one else wanted to talk about anymore. My mother will be eighty-one this year, and if I try to ask her about something troubling from our past—my absent and estranged father, the lynching of family members back home, what it was like growing up in segregated Mississippi, or what it was like when she first came to Chicago—she will say, “I don’t want to talk about that.” I’ve heard that same answer my entire life. If any of my first cousins tried to bring up something from the past, my mother would ask, “Well, why do you want to talk about that?” Or my aunt Myrtle, my mother’s only sister, would remain silent and simply shake her head. But Aunt Beulah would talk about whatever it was and seemed to enjoy talking. Somehow she was wired differently from all the women on my mother’s side of the family—this was mostly a clan of women, the men were emotionally distant or physically gone, strangers—maybe because she was the oldest and for that reason the voice of authority. Why did the others—my mother, my aunt, my grandmother Addie, my aunt Judy, and my aunt Koot—feel so uncomfortable about the past? I think there are many African-American families that feel you should forget about the past and try to leave all of that stuff behind. (All this talk about post-racial America is only an extension of that sense of shame and embarrassment, that need to forgot the horrors of a painful history. Americans seems to believe too simplistically in this idea of “closure” that we hear so often about on talk shows and such.) Beulah was the type of person who would never let those things go, although she was the most physically weak of the women, had almost any ailment you can name.

LAURA: You can’t completely divorce yourself from the past. I remember reading that the stories remain in your DNA even if you don’t openly discuss them. (My mother is from Little Washington, North Carolina and my father is from Virginia. They never liked to talk about the past.) But my version of your Aunt Beulah was my Aunt Robenia. She would tell those truths. She would start talking and was then quickly silenced. She wasn’t the most assertive person so her sharing was cut short, but I would get the full story later.

JEFF: Part of what inspired my first novel was an attempt to try to find out what made my family the way that it was. I mean, it was 90% fiction, but some of the characters are based on members of my family. We were screwed up in a way that was obvious to me. The only way I could figure it out was to take some of the things I knew about my family and try to develop stories. Those few facts became points of improvisation for writing fiction about those things. I strongly believe that our history of race has really shaped us, whether we acknowledge it or not, in ways that we usually don’t acknowledge, that it’s not so easy to get away from.

LAURA: You speak about improvisation and improvisation came up again during your interview with Wideman both in Black Renaissance Noire and Poets & Writers. There is a quote…let me see if I can find it. “In talking and telling Wideman, I am also telling myself.” Can you expand on that a bit more?

JEFF: I think that, among other things, what I was trying to say was that Wideman and I share similar circumstances, in coming from a poor family, in being first generation collegians, in having absent fathers. Those are some of the same parallels. But we are vastly different in many other ways.

LAURA: Wideman mentioned that he had to search for the silence because he had such a large extended family. He needed the silence.

JEFF: I come from a very small family, so it is just the opposite.

PAUSE (Dinner break)

JEFF: I really wish I could be more prolific. I don’t know how they do it, Phillip Roth, Joyce Carol Oates, Percival Everett.

IVELISSE: Joyce Carol Oates. . . . I need time to let it unfurl.

JEFF: I heard Jonathen Franzen give a talk recently about his latest novel, Freedom. He started thinking about it in 2000, but he carried the story around in his head for years and years. Eventually it took him only 6 months to a year to write what became the final book. But he thought about it for 10 years. Sort of like Edward Jones and The Known World. Carrying a story like that around for years in your head is a kind of revising process. Faulkner had a similar experience with Absalom, Absalom!

IVELISSE: I like the security of having those pages. I feel better because I have those pages and I can move forward.

JEFF: I think that’s how most people operate, including myself, although I do a lot of note-taking and pondering.

LAURA: You once shared that your classmates called you the Black Kurt Vonnegut. Vonnegut dealt with the fantastic in literature and the fantastic in daily life. When you look at his childhood, his young adulthood, you see his mother committed suicide when he was home on leave in 1944, his sister died of cancer within hours of her husband who died in a car crash. So when you look at how the extraordinary can occur in daily life, were you drawn to the fantastic because of real life tragedies or was it strictly your imagination at play?

JEFF: That’s a great question. I wish that I could say that I had all of those kinds of great tragedies happening, but no. (laughter) Like a lot of teenagers, I was reading science fiction and, at some point, I encountered Kurt Vonnegut’s name as a novelist of speculative fiction. SF writer Harlan Ellison used to write a lot of introductions to his short story collections and also edited two important anthologies of experimental science fiction. He mentioned Kurt Vonnegut and one or two of his novels. So I picked up one of his novels, Slaughterhouse Five, I believe, and found that he was just so funny. So I started reading all of his work. The reason why folks in college called me the Black Kurt Vonnegut was because I was writing humor. I was trying to be a satirist. Eventually, I decided that it wasn’t what I was best suited at.

I had the opportunity of meeting Kurt Vonnegut in person and spending the evening with him back in 2001, not long after the war in Afghanistan started. The Chicago Public Library gave us both awards that year. We were the only two honorees, Vonnegut for the body of his work over a lifetime, and me for Rails under My Back. One writer at the end of his career, and another at the start. He gave the funniest acceptance speech, talking somehow about Mrs. O’Leary’s cow who kicked over a lantern and started the Great Chicago Fire and the war. We had a drink afterwards in the hotel bar where we were both staying and the thing I remember is that he invited his two best friends from high school to the event. Some sixty-plus years of friendship. We had a conversation about writing. He was very encouraging. I felt that it had all come full circle, having the opportunity to meet him.

IVELISSE: How did you feel meeting him?

JEFF: I was a bit nervous at first, but also excited. Of course, he had all this money, but he was walking around the hotel wearing this old crummy sweater. It had holes in it.

LAURA: Was that his favorite writing sweater?

JEFF: Must have been. And he signed his book to me, and drew a little funny picture of himself. I don’t know if he did this with all his signatures, but he drew this little image of himself and then signed “Kurt Vonnegut” in barely legible handwriting.

LAURA: I read about his graphic work.

JEFF: I still like to read him. I think that he is one of America’s funniest writers.

LAURA: Do you dabble in areas outside of writing? Do you paint, sculpt?

JEFF: No, unfortunately, it’s hard enough for me just to get the writing down. At a certain point in my life, I played guitar a bit and I was a real chess enthusiast. Now I just have the normal hobbies. I read, I like music, go hear live music every now and then, I go to movies and museums on occasion, and I like to travel. Of course, I spend as much time as I can with my family. That’s pretty much it.

LAURA: Can you recommend any foreign films? There is a lot of buzz surrounding Beautiful, the film with Javier Bardem. Haven’t seen it yet.

JEFF: That’s the one where he plays a father. No, I haven’t seen anything recently. The last one I remember was White Ribbons, set in Germany during World War I. The director Michael Haneke did some other great films, The Piano Teacher and Cache. I also watched a Halle Berry movie recently, Frankie and Johnny. It was pretty awful, and she was pretty awful in it, bad overacting. Says a lot though because she was nominated for an Oscar for her role. I think this country often expects the mediocre from us, and when we give it to them they reward and celebrate us.

LAURA: What was the film about?

JEFF: She plays a woman with multiple personalities. She is usually very good, but this was really bad, pretentious and pointless, and unresolved even at the end in a glaring way.

DESSERT arrives

IVELISSE: This is a good end to a tough day.

JEFF: There is a good pastry shop not to far from here, a famous Italian joint just around the corner there on Bleeker Street. I can never remember the name of it. Oh yes, Rocco’s. It’s been around a long time. They have the best selection of everything—tiramisu, tarts, and fresh gelato. We all should go sometime.

[SINCE THE INTERVIEW, THE CITY HAS FORCED ROCCO’S TO CLOSE.]