"That's Us. That's Us." María Fernanda Snellings Interviews Maceo Montoya

Maceo Montoya grew up in Elmira, California. He comes from a family of artists, including his father Malaquias Montoya, a renowned artist, activist, and educator, and his late brother, Andrés Montoya, whose poetry collection The Iceworker Sings and Other Poems won the American Book Award in 2000. Maceo graduated from Yale University in 2002 and received his Master of Fine Arts in visual art from Columbia University in 2006.

Montoya’s paintings, drawings, and prints have been featured in exhibitions throughout the country as well as internationally. His artwork has appeared in a range of publications, including seventeen drawings in historian David Montejano's Sancho's Journal (University of Texas Press 2012), an ethnography of the Brown Berets in San Antonio. Montoya also collaborated with poet Laurie Ann Guerrero to create a series of paintings based on sonnets dedicated to her late grandfather. The resulting book, A Crown for Gumecindo, was published by Aztlán Libre Press in 2015.

María Fernanda Snellings interviewed Maceo Montoya on Wednesday, November 26, 2016.

MARÍA FERNANDA SNELLINGS: Let's discuss your artistic collaboration with poet Laurie Ann Guerrero. Are collaborations a reoccurring practice for you? Are collaborations important for young artists?

MACEO MONTOYA: The most important thing I gained from my experience working with Laurie Ann Guerrero was the insight into her creative process, glimpsing how she crafted her narrative. Collaboration can help a poet or an artist unpack the mystery, or the emotional core, of an image. And that’s essential, whatever your medium. I saw her search on the page, which aided me as I sought the form on canvas.

I recently finished a visual/textual project with Fresno poet David Campos and it has probably been the most organic of these collaborations. With David, he and I started with a simple idea of let’s work on something. When we began it sometimes felt as if we were competing with each other; he would send me five poems and in response I would send him ten images based on those poems, and he’d come back at me with even more poetry. We didn't necessarily know what we were after, only that we were both responding to this world we were creating together. By the time we finished – exhausted ourselves, really – we had 30 images and a manuscript entitled “American House Fire.”

One of my books, Letters to the Poet from His Brother, published by Copilot Press, is a mix of essays, prose poems, and visual art. I had been looking for years for ways of combining my writing and my artwork, but I didn’t know the first thing about making a book or putting one together in terms of layout. Impressed with some of Copilot Press’s previous publications, I approached the publisher Stephanie Sauer about working on this project with me. She agreed and, through her, I was exposed to this whole history of how to use the layout of a book to create an experience, whether through imagery or text or the material of the object itself. Collaboration opens up new approaches and ways of creating, and all of these experiences remain with me once I return to the solitude of my own process.

MARIA FERNANDA: To open the word "responsibility" with you, how have other Chicanos responded to your work?

MACEO: The idea of “responsibility” is something that I continue to sort through. I was born into a family of artists and I recognize and cherish the contributions that they made to the Chicano Movement and to Chicano Art. The legacy that my uncle José Montoya left behind and that my dad Malaquias continues to forge is still important, and I want to share that with people. I want their images and their words to live on. I know how fragile their legacy is. Like any artist, but especially artists working in the margins, they can so easily be lost to history.

I also know that my own freedom as an artist – in terms of how I approach the page or the canvas – exists because of the work that they created almost fifty years ago. They were the ones who truly had to battle against being silenced, ignored, or the reality of existing completely off the map. I feel a responsibility to represent that struggle, to remind others that it wasn’t that long ago that the Mexican American community thought of themselves as less than and certainly not the subject of Art or the creators of it. Chicano artists were the first to chisel away at that falsehood. But recounting the stories of the past, as important as they are, can also be exhausting. Sometimes you just want to move on, to talk about what interests you without having to reach back into history. I’m an artist now, why must I feel such anxiety about the actions and aspirations of young men and young women decades ago? But I’m torn because erasure is real and it’s frightening. I teach in the Chicana/o Studies Department at UC Davis and so many of my students have never read a Chicano poem or novel, they have no knowledge of the role that Chicano activists and artists in the 1960s and 70s had in paving the way for them to be there today. As an educator, I can offer a corrective and expose them to those contributions.

As far as how other Chicanos respond to my work, I don’t know, to be honest. I’ve always tried to be true to myself and to my instincts as an artist. I never wanted to feel as though I couldn’t push my work in a certain direction because I was worried about how it was going to be received. That being said, it has always been important for me to know why I was creating something. For a long time I was working on a series of paintings depicting scenes from Woodland, CA, which is home to a large immigrant population. Field workers were featured prominently in the work and I felt that my paintings were giving a voice to those that are silenced, whose stories aren’t told. In other words, I had a clear why.

Later, though, I started working on a series of paintings that were almost surreal in nature; some were figurative, some were dominated by the landscape, but I couldn’t say why I was painting them. There was simply an emotion I wanted to evoke and once I felt I had captured it, I would set the painting aside. During this process, I'd ask myself over and over What is this painting really about? And I didn’t know. I come from a Chicano Art tradition where it's largely about the socio-political implications: Whom are you trying to reach? What’s the message you're trying to convey? And here I was making work that felt entirely elusive.

I had an exhibition at a community gallery in Stockton, CA, and I showed a few of the paintings from this series. Stockton is a city that has struggled for many years and even entered bankruptcy mediation. I was at the gallery for the opening and a man who kind of looked down on his luck approached me and asked if he could share something with me. He led me over to one of my paintings that depicts a group of people in an irrigation canal, their faces all turned toward the setting sun. It’s called “Mistaking Every Sunset for the Rapture.” It was an image that emerged from my subconscious. I painted it, hoping I’d understand it, discover the why, and I never did. But the man pointed to the figures in the painting and said, “That’s us. That’s us.” He knew what the work meant; he didn’t need to know why I’d painted it. It’s important to have faith in the process. I have to remind myself of that. I have to follow whatever it is that is spurring me forward, propelling me further into the work, not worrying about meaning, or my ability to grasp that meaning. I’ve learned, thankfully, that the work is often much wiser than its maker.

MARÍA FERNANDA: We create identities for labels. “Chicano” demonstrates self-possession. Can you describe this in your work?

MACEO: I think labels are always flawed. You can always push for a more inclusive understanding of that label or identity, but there will be those who claim ownership of it, who try to define it, who seek to be the gatekeepers for that label. This power-struggle can make people uncomfortable and it should. We should be skeptical of labels. These are terms that were man and woman-made and must evolve and expand if they’re to remain relevant.

What I think is incredible about “Chicano” is that, from the beginning, it was used as a term that brought all of these different, often contradictory strands together. It put a name to an experience, to how people lived. It wasn’t just designating two languages, two countries, or a hyphenated existence. No, this label defined how people experienced their world, their culture, and their history. I think it’s that “how” that allows the term “Chicano” to account for an ever-widening swath of experience. We’ve always crisscrossed literal and metaphorical borders. As a storyteller, this is an exciting and complex space to mine.

MARÍA FERNANDA: Your manipulation of scale in paintings such as, “Father and Son (Desert Crossing)” is amazing. Could you describe the physical environment you grew up in, your family driving you to rallies and how that influenced your paintings?

MACEO: I grew up in Elmira, a small town of three hundred people, surrounded by fields. My parents still live there. It’s completely a part of me. At the same time, my family had many connections to the Bay Area, and we would often go there for political rallies or cultural events, sometimes for my dad’s exhibitions, or maybe we’d go to Sacramento for my uncle’s poetry readings. I also have family in Southern California as well as on the East Coast. So I always had the ability to travel to different places. Being exposed to these other worlds meant that I never felt confined to Elmira.

I see so many young people in small towns scattered throughout the Central Valley who feel suffocated in their surroundings and that’s because they don’t see a way out. For me, that was never an issue. I always knew the world was out there, and so I feel that my experience was somewhat different from other small town kids. That being said, I’ve never been able to shake the feeling, no matter where I’ve been, that I’m just a kid from this nothing town. To this day, there are only eight streets, and sixty houses, and my elementary school that closed down years ago, but I hold it all so close. That’s what I mean when I say that Elmira is completely a part of me.

When I was in New York for graduate school, I found it difficult to create. It wasn’t until I started thinking about images from back home, from the landscape I was most familiar with, that I was able to create again. I think some artists can draw inspiration from wherever they are, but I’m someone who has to be rooted in place.

As an artist and fiction writer, I tell other people’s stories. I do so because I want to look beyond my own limited experience and frame of reference. But I’m most comfortable doing that within a landscape I know well, in a setting where I know I belong. We are always striving for approximations of experience, and for me, the best place to start is discovering what’s held in common, and what can be more shared than people inhabiting the same space? From whatever distance, they’ve seen my life and I’ve seen theirs. Maybe we grew up together; maybe they watched me grow up or grow older. Maybe we have no connection except that we live our lives walking the same streets, surrounded by the same familiar markers, we’ve stared at the same landscapes— I need all of that in order to feel comfortable telling someone else’s story, otherwise I feel too much like an interloper.

MARÍA FERNANDA: When discussing your fiction, you’ve spoke of this concept of “the exterior pose versus the inner turmoil.” When approaching the canvas, do you consider this balance between peripheral and core narrative?

MACEO: As I mentioned, I need to feel a deep connection with the subjects of my work. I want the freedom to invent, to fictionalize, but I want the work’s core to be true. By that I mean, even if I’m creating a scene completely from my imagination, I need it to rest on something incontrovertible, something I’ve witnessed or lived through. I can easily invent a face, I can imagine a dramatic scene – that’s all exterior, the surface – but it’s infinitely harder to fabricate the emotional center of a piece.

MARÍA FERNANDA: This reminds me of your painting “Solemnity of a Madman’s Last Possessions,” a piece included in your series Cantos of Sorrow, which was inspired by dreams, visions, and memories, while the people portrayed are mostly fictional. Could you talk about this more?

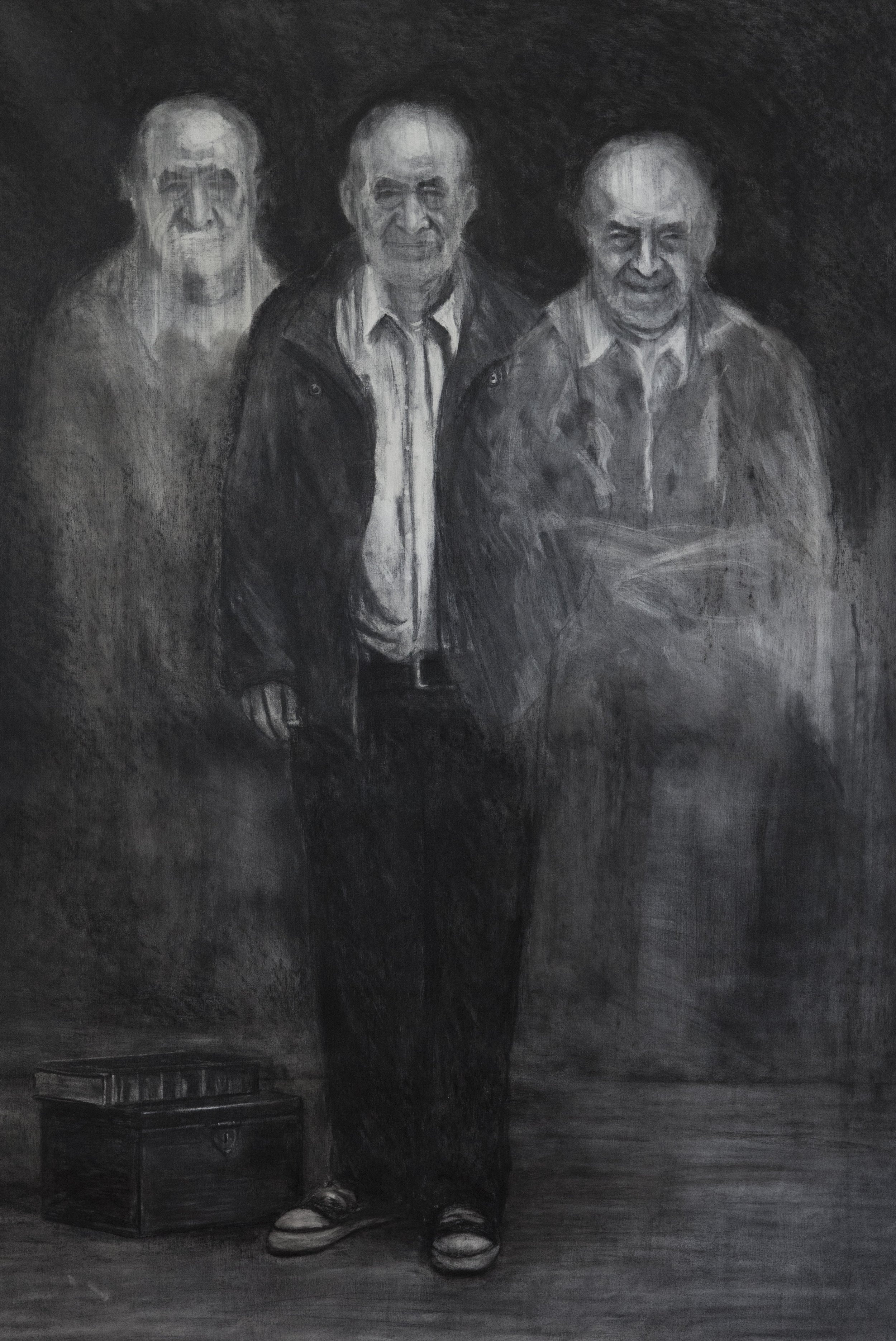

MACEO: The painting “Solemnity of a Madman’s Last Possessions” is based on my uncle, my Tío Jimmy. He suffered from schizophrenia and was completely dependent on the family. Yet, he was the oldest brother and when we went to visit him in his assisted living home I saw my dad transform into the little brother. We would laugh later at some of the things my uncle did or said, but it was always laughter tinged with sadness. When he died, all he left behind was a Spanish-English dictionary, a magnifying glass, and enough trinkets to fill a small box. The paintings in the series “Cantos of Sorrow” are all based on memories that I then fictionalized or transformed in some way, usually for dramatic effect. My uncle’s story didn’t need elaboration.

I need to stand on a strong foundation and feel as if I’ve covered my bases before I’m able to set off and do what an artist does…invent, imagine, create. That’s always been important to me. I’m often afraid of getting the story wrong, of misrepresentation. Artists can strive for honesty or authenticity, but it’s not a given. If you live in between worlds you understand that. If you’re biracial or Chicano or you live between languages, you know that you’re always posing to one degree or another. Your authentic self is colored by the constant feeling of inauthenticity. You’re always searching for your place in other people’s worlds. In some ways, you’re always on guard, your senses heightened. That’s not a bad place to be, especially as an artist. It just means that I always want to tread cautiously, to double-check my work, to make sure that I haven’t erred in representing the lives of people about whom I care deeply despite the distances that may exist between us.

MARÍA FERNANDA: In a previous interview, you’ve remarked, “There’s this idea that one must leave to discover oneself, but it’s often the return that forces the discovery.” How does this manifest among your students at Taller Arte del Nuevo Amanecer (TANA)?

MACEO: It goes back to the responsibility of the artist. There’s this assumption that places like Elmira, where I grew up, or the Central Valley, or Woodland, where I live now, are devoid of culture, that they’re wastelands of sorts. Many progressive, intelligent people think that the only place to find culture is in the Bay Area, or New York, or Los Angeles. But I’m not in any of those places, and yet I’m surrounded by beautiful people with compelling lives and incredible stories that remain untold. I know this for a fact. I set two of my novels in Woodland. Much of Letters to the Poet from His Brother takes place in small towns in this region. This is the source of my creativity. But it’s not enough for me, alone, to be telling these stories. I want to encourage it in others. I want them to find their voice and to feel that Woodland and these other forgotten or overlooked places are not solely to be escaped from, that the stories of their community also deserve to be preserved and memorialized.

Whether through visual art or writing down stories, teaching young people to find their voice can give them a real power, a real control. And that can be their escape. They can transcend their circumstances through language, through imagery. My teaching, whether on campus or my work at TANA, is driven by a desire to empower, to give others the tools that I find so necessary to survive in this often troubling world.

MARÍA FERNANDA: How have the election results affected your visual art?

MACEO: When people think of Chicano Art and its history, the artist’s role is to respond directly to political events. My dad Malaquias has already made posters about Donald Trump, about this fear that so many are experiencing. And yet, very early on, I think I started to realize that I didn’t feel comfortable responding so directly and immediately. I wanted a slower approach. I wanted to seek out the specific, intimate story. Instead of responding first, I wanted to hear the voices that surrounded me.

So, yes, Trump is part of our political climate, his actions will have a frightening and direct impact on so many, but as an artist, I’m more curious about how his actions will make their way into the fabric of our daily lives. I don’t know how that will emerge in my fiction or in my visual work, but whatever response I have will be a slow meditation on what I see happening around me. That doesn't mean I’m not filled with turmoil; it’s just that my artwork needs time and patience to develop. I want to better understand what it is that we’re grappling with.

MARÍA FERNANDA: Not forcing our personal truths is important. If we, even as multi-genre artists, are not directly responding to every sweeping political moment, then we must keep sharing our stories and listening to each other.

MACEO: It’s true. I started writing my second novel, The Deportation of Wopper Barraza, in 2008, and it was based on a story that I had overheard. Wopper, the main character, was brought here [to the United States from Mexico] when he was three years old and then deported in his early twenties. It happened to a friend of a friend and I fictionalized it. In the end, the novel became more than just one man’s story; it was also about how the deportation affected his family—his girlfriend, his parents, and other community members—it became very much a Woodland saga. As I was writing the book, I was thinking more about the drama of the story and not necessarily about its political context, and yet, because of the times we’re living in, it’s a completely political book.

We’re dealing with the very real impact of deportation and the imminent threat of it. I’m afraid for some of my students who benefited from DACA [Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals]. They’re now fearful that they’re going to have to go back into hiding. Because of our current political climate, suddenly my novel has gained a certain relevancy— we’re seeing stories similar to Wopper’s in the headlines. But if Wopper, as a character on the page, wasn’t a fully-fledged human being, then his story would cease to be consequential beyond the political moment. I think that anyone who has written a novel knows it usually takes years to write, even more years to get published. It would be impossible to persist through that process if you’re constantly responding to the political “flow.” The importance of any story will derive from the honest depiction of its characters, because the lives represented are complex and whole, not because it’s a timely response to a figure like Donald Trump.

MARIA FERNANDA: Thank you for taking time to allow us to interview you. It’s so important to us.

MACEO: I appreciate these exchanges. I think artists need to be forced to contextualize their work otherwise these ideas are just floating around in our heads. These conversations help me to reflect on what I’ve done, and where I’m going, so I thank you.

Contributor Notes

Maceo Montoya grew up in Elmira, California. He graduated from Yale University in 2002 and received his Master of Fine Arts in painting from Columbia University in 2006. His paintings, drawings, and prints have been featured in exhibitions and publications throughout the country as well as internationally. Montoya’s first novel, The Scoundrel and the Optimist (Bilingual Review, 2010), was awarded the 2011 International Latino Book Award for “Best First Book” and Latino Stories named him one of its "Top Ten New Latino Writers to Watch." In 2014, University of New Mexico Press published his second novel, The Deportation of Wopper Barraza, and Copilot Press published Letters to the Poet from His Brother, a hybrid book combining images, prose poems, and essays. Montoya also collaborated with poet Laurie Ann Guerrero to create a series of paintings based on sonnets dedicated to her late grandfather. The resulting book, A Crown for Gumecindo, was published by Aztlán Libre Press in April 2015. His most recent book, You Must Fight Them: A Novella and Stories, has just been published by University of New Mexico Press.

Montoya is an assistant professor in the Chicana/o Studies Department at UC Davis where he teaches the Chicana/o Mural Workshop and courses in Chicano Literature. He is also the director of Taller Arte del Nuevo Amanecer (TANA), a community-based arts organization located in Woodland, CA.