guest-edited by Jeffery Renard Allen

Being an African in our home was not a problem at all. It was effortless, as easy as breathing. Being an African outside of our home, now that was difficult. Actually, it wasn’t so much the being African part that was problematic, it was the not being American part. I didn’t like standing out, having other kids determine, by the way I spoke or dressed or styled my hair, that I was different: an outsider, an interloper, an alien. So I tried, as best I could, to blend in.

Every Fourth of July, I took part in the small Takoma Park parade. I would wake up just as the sun was also rising, put on my sleeveless red leotard and a brand new pair of ultra-white ankle socks and tennis shoes. My long jet-black hair was always pressed straight with a hot-comb for the occasion, and Mum would fix it into two pigtails that inevitably ended up being uneven. After getting dressed, I’d grab my baton, which was decorated at both ends with small strips of royal-blue ribbon, and then bolt out the front door.

The starting point of the parade was downtown, right in front of the fire station on Carroll Avenue. This was in the mid-1970s, long before the subway station was built or the co-op was established. Downtown Takoma Park was barely two blocks, a typical Main Street USA, with mom-and-pop shops in red-brick buildings—a barbershop; an ice cream parlor; and, a hardware store, where they copied keys and sold square head lag bolts and handmade one-piece hammers.

As soon as I got there, I would squeeze myself into the huddle of other red-leotard girls. Once a respectable crowd had gathered, the band would play while stepping in place, and we amateur majorettes would take our positions—right leg bent, left hand on hip—and wait for the cue, the musical run that signaled us to start marching and twirling those silver wands high atop our heads.

A few years back, when I had only recently emigrated from Ghana, when the life I’d left behind was still so clear, so close, just a casual glance over my shoulder, all I wanted was to go back. I wanted to explore America and the many magical things it had to offer: the snow, the sea horses, the Archie and Veronica comic books; Soul Train, Schwinn bikes and Steak-umm sandwiches. I wanted to take every single bit of it in, to package that excitement of newness and that wonder of discovery, carry it back to Ghana with me and share it in story.

It soon became obvious that I would not be returning, though to hear my parents speak you’d think our departure was imminent, that we had tickets in hand and needed only to pack our bags and offer our farewells. I was scolded whenever I behaved in a manner that was deemed “too American,” reminded that I was not “one of them.” I was made to understand that despite the backdrop of small town America, I was an African girl having an African childhood. What choice did I have but to accept it as truth?

Nevertheless, I learned to take their talk of return at face value. Whenever my parents began their sentences with the words When we go home I simply convinced myself that they were drifting into fantasy, declaring a hope or wish they wanted to manifest in a future that was too distant to even plan.

Home was a word I learned to define by context clues. Sometimes it meant Ghana, other times it meant Takoma Park. I was caught betwixt and between a place I could now barely remember and a place that I wasn’t allowed to fully adopt. What I now wanted more than anything was to belong somewhere, to fit in and become an accepted member of the community into which I’d been thrust. Trying out and being chosen to be a majorette in the annual Independence Day parade was one way; submitting my name and being chosen to be a safety patrol was another.

Each afternoon before leaving school, I would strap on a glowing pumpkin-orange belt that went over my right shoulder and around my waist. Pinned to the belt, a little beneath my collarbone was a shiny, official-looking silver badge that, for the brief time I was wearing it, transformed me into an authority figure, a leader, someone to be respected and taken seriously.

When the bus pulled up to our stop at the intersection of Carroll and Flower avenues, which also happened to be the last stop on its route, I was always the first one off. I would stand at the edge of the curb and face the yellow bus as it idled noisily and spewed thick grey smoke from its exhaust. “Okay, you guys can start crossing,” I’d tell my schoolmates who were standing in the aisle of the bus waiting for me to give them the “green light.”

As they were getting off the bus, I would hold my right arm high, outstretched horizontally, the muscles tightened, the palm pressed flat against a wall of air ordering everyone and everything to stop. At the same time, my left arm would be lowered, bent at the elbow, swinging back and forth, the hand waving my schoolmates across the wide street. As soon as everyone was off the bus and the last student had safely stepped onto the opposite sidewalk, the driver would glance at her side mirror to make sure it was safe for me to then cross. She would move her eyes to meet mine and then nod to let me know that I was being relieved of my responsibility. I would sprint across the street and join my friend, Jennie Potter. Even though she only lived a few houses down from the intersection where the bus stopped, every day Jennie would perch herself on the steps of the corner house, waiting patiently for me so that we could walk home together.

The bus stop was just about three or four blocks from the apartment where my parents and I lived. Back then I was what was known as a latch-key kid, a child for whom no one was waiting at the end of the school day. I wore a cheap metal chain around my neck, on which the key to our front door hung like a charm. After I had let myself in, I would phone my mother at work to tell her that I’d arrived; then, as soon as I’d completed my homework, I’d phone her again, this time to ask if I could go hang out at Jennie’s house.

Jennie and I met in second grade, the year my family moved to Takoma Park. We sat next to each other in class, and once we discovered that we were pretty much neighbors, she and I gradually inched our way into a friendship. Jennie, her eight siblings, and their parents, lived in a Craftsman that was so large it dwarfed the modest ranch-style homes on either side of it. I used to spend most of my free time after school at the Potter’s. I loved being there because it was always squirming with activity: televisions blaring, music blasting, dogs barking, kids teasing, playing and arguing.

Many of my parents’ friends—other Ghanaian immigrants, educated people who had been trained as doctors or nurses, lawyers or accountants—took menial, low-paying jobs to make ends meet.

Jennie’s parents didn’t work. I realize now that they were probably retired, on welfare, or some combination of the two; but I had no way of knowing that as a child. When I first started hanging out at Jennie’s house, I used to think I’d probably caught her parents on their day off, but then I noticed that they were always at home so I just concluded that they didn’t have jobs, which, for me, was unheard of. My father worked long hours at the Ghana embassy and my mother, who was pregnant, also worked. Everyone I knew who was old enough to have a job did, and usually they had more than one. Many of my parents’ friends—other Ghanaian immigrants, educated people who had been trained as doctors or nurses, lawyers or accountants—took menial, low-paying jobs to make ends meet until they could either reinvent themselves or figure out a way to make their prior credentials count for something in their new country. They worked as bell hops, nannies, taxi drivers, burger flippers, cashiers and gas station attendants. I simply assumed that Jennie’s parents didn’t work because they didn’t have to, because they were rich. How else, I reasoned, could they afford to sustain such abundance—a three-story house, two cats, two dogs, two cars, nine children and their many friends?

Being inside the Potter home was what I imagined it might be like inside the home of one of those television families I so loved, like the Brady family or the Waltons, or even the Ingalls from Little House on the Prairie. The Potter family’s wealth, or what I imagined to be their wealth, merely added to the allure. There were three boys and six girls, all of whom were boldly blonde, of medium height, with perfect white teeth that looked like Chiclets. Each of them had names that ended in ie or y, names like Scotty and Ronny and Pattie and Kimmie, names that, once they hit high school, they shortened to Scott, Ron, Pat, Kim, and Jen.

The Potter home was not at all like the calm, traditional feel of my home. The two realities were as far apart as they could possibly be, each one an absolute, almost obscene, reflection of the culture it sought to represent. Nearly everything about us, and our way of life, was reminiscent of Africa. So much so that I avoided talking about myself, about my family, and I habitually lied about the smallest things, like what I’d eaten for dinner. My parents and I lived in a cramped two bedroom apartment, the walls of which were decorated with fabric, animal skins and hunting paraphernalia: there was a large Adinkra cloth; the long, dried out skin of a baby python snake; the bristly fur coat of a wildcat--complete with its tail, head and all four limbs; two bows, inside of whose open arcs hung two rough leather pouches, each one holding ten poison-tipped arrows. There were statuettes and small wooden carvings on the end tables and other flat surfaces. A hideous beige fabric couch was the only piece of furniture that did not reflect our origins.

The Potters ate thin white slices of Wonder Bread and boiled-to-a-plump hot dogs on paper plates, kept disposable salt-and-pepper shakers and institutional-size containers of condiments on their Formica kitchen counter. Every piece of furniture inside the Potter home was scratched, chipped, lopsided or just plain broken. With all those people there, nothing had the chance to stay new and intact for long. There were no paintings on the walls, only framed school pictures of the kids and nearly two decades’ worth of Sears studio portraits of the family. Every surface in the house was cluttered with toys, pens, combs, bobby pins, nail clippers, magazines, and thick romance novels—with sultry women in revealing poses on their covers—the inside pages of which were usually dog-eared and dirty with chocolate and ketchup stains.

The meals my mother prepared for me were the same ones that she grew up eating—fufu and light soup with goat meat, banku with okro stew, jollof rice, kenkey with fried fish and a mouth-burning pepper sauce.

Unlike Jennie Potter, I could never throw open the cupboard doors, grab a bag of potato chips, a can of Campbell’s soup, then pull a pizza and Salisbury steak t.v. dinner out of the freezer and ask my guests to decide which ones they wanted to eat. We never kept that sort of food in my home. The meals my mother prepared for me were the same ones that she grew up eating—fufu and light soup with goat meat, banku with okro stew, jollof rice, kenkey with fried fish and a mouth-burning pepper sauce. Sometimes Mum would make the sauce, which is somewhat similar to a Mexican salsa, by throwing all the ingredients into a blender; other times she would sit on a low stool and grind them together in a big clay mortar with a wooden pestle that looked more like a musical instrument than a cooking utensil. Every so often, she would drive to some farm out in the countryside and buy live chickens. She would bring the squawking birds home, kill, pluck and cook them in our tiny kitchen.

The commotion and carefree atmosphere of the Potter home fascinated me. They were the first real American family I knew and I thought their lifestyle was a true example of everything America represented, the dream in its entirety.

Jennie’s parents chain-smoked and cussed in front of their kids; they used words that I had never heard slide out of my parents’ mouths, words like shit and fuck and bitch. And once they started to feel at ease around me, they used nigger, too.

“I almost got into a fucking car accident today,” Mr. Potter said one afternoon. “Some goddamn nigger pulled out, wasn’t looking where he was going.” I was nine years old, in the fourth grade. It was autumn and the weather had started to turn soggy. Jennie and I were sitting at the kitchen table eating peanut butter and raspberry jelly sandwiches. Groundnut soup is one of my favorite dishes, and I have always loved eating peanuts with roasted plantain, but before I came to America, to Jennie Potter’s house, I’d never eaten peanut butter. I absolutely hated it, couldn’t stand the pasty texture, the way it adhered to the roof of my mouth. But I had been taught by my mother that if you were a guest in someone’s home, it was rude to refuse an offering of food. So I sat, stern-faced, and struggled to swallow bite after nauseating bite of the sandwich.

“Dad,” Jennie whined, slightly tilting her head and rolling her eyes toward me to remind her father that I was present and could hear his comments. Suddenly flustered, Mr. Potter studied me for a few seconds and then turned his gaze to Jennie.

“You said she’s African, right?” His voice was deep, rough and grating as sandpaper.

“Well, yeah,” was Jennie’s response. She looked over to me as if she was waiting for me to say something that would either confirm or contradict that assertion. I stayed silent. At that point, I was more curious than uncomfortable.

“Then she’s got nothing to worry about.” He took a slow and deep drag from his cigarette, which he held firmly between the thumb and index finger of his right hand. He squinted his eyes as he held in the breath and then opened them as he exhaled from the left side of his mouth.

“You see,” he began, releasing the last wisps of smoke around the words. He walked over to where we were. I didn’t look up, but I could feel him standing beside me, wedged into the small space between Jennie’s chair and mine. “It’s true that all niggers are black, but what a lot of people forget is that not all blacks are niggers. Africans are Africans. A completely different breed, straight out of the jungle. You guys aren’t like the common black folks we got here. And I’m sorry to say, a lot of them are niggers, just no good. Nah, if you hear us talking about niggers, don’t think twice because we’re not talking about you.”

There really wasn’t much that I knew about that word, nigger. Since I’d heard some of the black kids at school toss it back and forth at each other, it hadn’t dawned on me that nigger was derogatory, a racial slur—not until Mr. Potter used it and I sensed the spite, saw the shame paint itself into Jennie’s cheeks. I felt that in his own way, Mr. Potter was trying, if only for the purpose of appeasing his embarrassed daughter, to assure me that I was not the object of his hatred.

“Thank you, sir,” I said, because that’s how we Ghanaians are—courteous and non-confrontational, especially children, who are taught to be respectful and polite to every adult, under all circumstances.

I broke off a piece of the sandwich with my fingers and shoved it into my mouth. I was trying hard to figure out the logic in what Mr. Potter said. I strung the words together, replayed them again and again, but they still failed to make sense. I wanted him to explain what it was about the black person in the car that made him a nigger. I didn’t dare ask, but I did wonder. Did being a black American automatically make him a nigger? Did being an African, being—as Mr. Potter claimed—of a completely different breed, automatically shield me from being a nigger? How could he tell the difference between the two? There were so many questions I wanted to ask, but I had a feeling that Mr. Potter was not the person to whom I should look for answers.

The decision to not tell my parents about my interaction with Mr. Potter was a no-brainer. I knew they would have been angry, if not about the use of the word nigger and the other profanity, then definitely about Mr. Potter’s claim that Africans—me, my family—were straight out of the jungle.

An intense pain began to bloom directly in the center of my forehead and my eyes started to water. I bit my lower lip to keep the tears from flowing. Suddenly, in addition to all those other complicated emotions, I started feeling sick, physically ill. My stomach was tight, cramping and in knots, a volcano threatening to erupt, and I wasn’t sure whether it was because of the exchange that had taken place, or the nasty peanut butter I had been forcing myself to eat.

The decision to not tell my parents about my interaction with Mr. Potter was a no-brainer. I knew they would have been angry, if not about the use of the word nigger and the other profanity then definitely about Mr. Potter’s claim that Africans—me, my family—were straight out of the jungle. My mother would have said “no” to my future requests to spend time at the Potter house, and my father, well, there was no telling what he might have done. As it turned out, within a couple of weeks I stopped going to their house, but not because of the things Jennie’s father had said. She and I were still friends. We still walked home together from the bus stop. I stopped going to Jennie’s house because my grandmother had come from Ghana to live with us for a while.

My grandmother, whom everybody—even her children and grandchildren—called Auntie Comfort, was my sometimes disciplinarian and my most times confidante and co-conspirator.

Mum’s delivery date was fast approaching so, as is customary among Ghanaians, her mother had come to take care of her and the new baby. Having my grandmother live with us meant that I was no longer a latch-key kid. I didn’t have to sit alone in the apartment until one of my parents came home, or walk those few blocks to the Potter house in search of company.

My grandmother, whom everybody—even her children and grandchildren—called Auntie Comfort, was my sometimes disciplinarian and my most times confidante and co-conspirator. She took great pleasure in bending other people’s rules, especially those set by her children for their own kids.

“You don’t worry,” was her standard response whenever I reminded her that she was letting me do something my mother had expressly instructed me not to. She’d clap her hands once then let them hang in the air, palms up, and ask, “What can she do? She is not the boss of me. I am her mother so I, rather, am the boss of her.”

Auntie Comfort is the one who’d accompanied me on my journey to America. She hadn’t returned to Ghana immediately; she’d stayed and lived with us for months and months. She and I were introduced to this new country together. We’d survived our first winter; we’d learned to sing commercial jingles and Schoolhouse Rock songs; we’d done it all side-by-side. And now that my beloved grandmother had returned, I fully expected that things would go back to the way they were when we’d first arrived. And boy, did they ever.

“What is that you are wearing?” Auntie Comfort asked nearly every morning as I was getting dressed to go to school. I gathered that she felt my clothing was too casual.

“But I’m just going to school,” I would explain. In matters of most everything, Ghanaians tend toward the formal. Far from being an exception to that rule, fashion is the crux of it. And nobody ruled fashion more than Auntie Comfort. The woman could out-dress anybody. Her beauty and sense of style were legendary. She had piercing eyes, onyx-colored pupils that swirled into a lighter, almost indigo shade at the edge of their outer rings. Her hair, long and electric-silver, was usually swept up into a beehive bun.

All of Auntie Comfort’s clothing was custom-made and, more often than not, designed by her. I loved watching her while she was getting dressed to go out. The way she breezed her hand against the fabrics that were hanging in the closet, as if she were communicating with the different textures, allowing her flesh, not her mind or her mood, to decide how it wanted to be adorned. Her jewelry was grand, the earrings long and dangling, nearly grazing her shoulders. They seemed to lengthen her face and neck, make her taller, more statuesque than she already was.

It was bad enough that I was skinny and bug-eyed, compared to Auntie Comfort I invariably looked sloppy, frumpy; but that’s who I was. Fancy outfits felt like costumes to me, awkward and unnatural, as if I were pretending to be something or someone I was not. I preferred trousers and t-shirts, and I usually tried to get away with not ironing them, which was a huge no-no. Nobody left our house wrinkled. Well, nobody was supposed to. Before Auntie Comfort returned, my parents never really noticed. In the mornings, they usually left before me, and even if they didn’t, I was almost always wearing a coat that covered up whatever I had on.

“Please change right now,” Auntie Comfort would demand. “You look like a peasant. You are not a peasant. You do not come from peasant people.”

“But Auntie Comfort, in America everybody looks like that,” I would whine, and then I’d stomp my foot and pout.

“Who is everybody?” she would ask. “Are you everybody? Nonsense. Leave those foolish people to their lives. You are not one of them. You are different.” With that, she would start going through my clothes to decide which outfit would best reflect my difference.

“Let me tell you something,” Auntie Comfort would say, pinching my pout into a pucker. “Every lady knows that it is better to be overdressed than underdressed. You will soon be a lady, a proper Ghanaian lady. You’d better begin behaving like one now. I don’t want you to start acting like these ruffians here.” With that, she’d release my lips and lower the pinch to my bum.

After about a month of trying to negotiate with Auntie Comfort, I gave up, figuring it was probably better for me to lose one battle than to end up fighting an entire war. The day I made the decision to raise the white flag was the day Auntie Comfort started to look beyond my clothes. I’d clipped off a little bit of my hair so I could have bangs, and then I’d tried to feather them ala Farrah Fawcett, my favorite actress on Charlie’s Angels.

“Oh, Nana-Ama,” Auntie Comfort cried out. She was frowning. “Your hair does not look nice. What have you done? Come here.” Instead of going toward her, I turned around and ran out of the bedroom and into the bathroom. I could hear her calling out behind me. “You look like someone who has just been struck by lightning.”

When I stared in the mirror, I could see that my grandmother was right; my hair looked awful. Still, I refused to go back into the room to let her fix it. She didn’t believe children should have their hair chemically relaxed, though she would allow a once-through with the hot-comb for special occasions. My mum would let me get my hair straightened once in a while, and I would do everything in my power to make sure it stayed straight for as long as possible, even if it meant skipping PE class and avoiding anything else that might make me sweat myself back to a natural.

When we first arrived in America, Auntie Comfort used to send me to school in afro-puffs or three loose braids, each of their ends adorned with a long piece of colored yarn that was tied into a bow. Or she wrapped my hair with thread and then gathered the individual pieces and wrapped them together as well so that when she was done it looked like the handle of a huge basket was protruding from my head.

I didn’t know what the word exotic meant, nor had I ever heard of the National Geographic magazine.

“How exotic,” one of my teachers told me, immediately putting both her hands in my hair. “It looks like something I once saw in the National Geographic magazine.”

I didn’t know what the word exotic meant, nor had I ever heard of the National Geographic magazine. That afternoon I spent my recess period in the library with the dictionary and a stack of the most recent issues of National Geographic. What I discovered was disturbing. I didn’t like it one bit. I never wore my hair that way again, and each time Auntie Comfort tried to make me, I protested like hell.

That morning of the failed Farrah hairdo, I rubbed a quarter-sized glob of Afro Sheen in my palms and then put it in my hair, allowing the pomade to smooth down all the cowlicks and errant strands. I then fastened the loose hair into a ponytail, hoping that when I emerged from the bathroom my grandmother would let me go to school without mentioning anything else about my hair. And that’s exactly what happened.

Soon enough, the semester was over, which meant no school for a few weeks. It was an instant reprieve from the arguments about proper attire. Auntie Comfort and I now spent our days watching All My Children, One Life to Live, and General Hospital. After that, we’d hop the number 17 minibus to join all the other bargain basement folks at Langley Park Shopping Plaza. We’d browse the aisles of boutique stores, maybe even buy a few things, before heading over to the Zayre Night Light Sale, where we’d stock up on all the gadgets she wanted to take back to Ghana with her, cheap items that would break or stop working and turn into junk long before the next Christmas season.

In the middle of January 1977, right before the end of my Christmas break, my mother gave birth to my sister, P. She was the first American citizen in our family. I’d always wanted a sibling and now finally I had one, though the nearly nine-plus-years age difference all but guaranteed that it would never quite be the way I’d scripted it in my only-child imaginings. The best part of it all, though, was that once school started up again, Auntie Comfort was too pre-occupied looking after Mum and the new baby to pay much attention to me, or my wrinkled clothing.

Something else happened that January, an event that startled me into a profound awareness of race and the crucial role that it would play in my new life. The event was Roots, the televised version of Alex Haley’s best-selling novel, which traced his ancestry back to its beginnings in Africa.

It was a mini-series, the first of its sort, with the shows presented every evening for eight consecutive nights. The first episode that aired took viewers through the birth and young adulthood of Kunta Kinte, a Mandinka from the tiny village of Juffure in Gambia, West Africa. The baby was sleeping and my father must have been our, or still at work. I only remember that my mother, grandmother and I sat in the living room and watched. It was refreshing to see ourselves on the screen, to see Africa, or that which the producers imagined was a close-enough rendition of Africa. I laughed at the editorial comments Mum and Auntie Comfort made during the show:

That is not the cloth of that tribe.

Is this how Americans think we live?

The accents are all wrong.

Whose bright idea was it to cast O.J. Simpson as an African?

Being there with my mother and grandmother, being able to soak in a few drops of their experiences and the sweetness of their nostalgia made me feel empowered, almost triumphant. The pride was coursing through my veins. For a moment, a blink between scenes, I understood that this pride, this sense of connectedness to my homeland, was what would sustain me. I was, and would always be, an African. That would have to define my future as much as it had my past.

And then suddenly on the screen, Kunta Kinte was captured. While out in the woods searching for a suitable log from which to build a drum for his younger brother, Kunta Kinte was spotted by a white man, a slave trader, who signaled his accomplices, four black men, to chase Kunta and hunt him down. The abduction was a heart-wrenching set of scenes, shown in several overlapping slow motion shots: Kunta Kinte flailing his arms, which were chained and shackled at the wrists, then screaming his agony into the sky before finally dropping to his knees and looking down, as if to beg for mercy from the earth itself.

“What are they going to do to him?” I asked, wiping a tear from my cheek. “Are they going to kill him?”

“I don’t know,” my mother said, the words barely escaping her throat. She was visibly shaken, as was my grandmother, whose lips were fixed in a silent, horrified O. We continued to watch, each scene more brutal and agonizing than the one before.

“You have school tomorrow,” Mum announced as the traders were loading Kunta Kinte and their other captives onto the slave-ship, the Lord Ligonier. “Change your clothes and go to sleep.”

I couldn’t believe Mum was making me keep to my regular bedtime. It seemed like such an act of injustice. I knew she didn’t want me to watch any more of the show because of the violence. As much as I wanted to stay right where I was, I complied without argument.

The following night, Mum and Auntie Comfort took their places in front of the television. After that episode of Roots began and I felt they were fully engrossed, I quietly sat on the floor and leaned my head against Auntie Comfort’s knee. Mum noticed me right away; she gave me a sideways glance, but didn’t ask me to leave.

The Lord Ligonier, tightly packed with its human cargo, was sailing the Middle Passage, en route to America. It arrived at a port in Baltimore, where the slaves were immediately offloaded and transported to Annapolis. There, they were inspected and then sold on the auction block to the highest bidder. My familiarity with those two locations, Baltimore and Annapolis, offered me a jarring frame of reference. I’d spent an afternoon in Annapolis once with my godmother, and though I had never been to Baltimore, I’d seen the name listed on several highway signs and knew that it, like Annapolis, was not far at all from where we lived.

As I stared at the activities on the screen, the thought of our proximity to those cities where such unspeakable acts had taken place, where such pain had been caused, frightened me. It was a bad dream sort of fear. I imagined myself one day being snatched from my family, being beaten and chained, taken to those auction blocks that were so close, too close, to the place I now called home. I tried to dismiss the fear by reminding myself that Roots was not real, that it had been based on a work of fiction. That consolation, of course, came undone when my mother released a long, mournful sigh, shook her head and said, “And they have the nerve to call us savages. Look at how they treated us. Look at what they did to us.”

“Is all this real?” I asked Auntie Comfort, tugging at the hem of her housedress. “Is it a true story? Did this really happen?” My questions hung desperately in the air for a few moments before they faded gently into a solemn cloud of silence.

We continued to watch as Fiddler, an older American slave, selected and paid for Kunta Kinte on behalf of his master, John Reynolds. The transaction was barely complete when Reynolds decided on an American name, Toby, for his freshly purchased slave.

Us, I thought as I stared at Kunta’s trembling lips; Look at what they did to us. There was such power in that word, us. It was large and binding, and unbreakable.

“Yes,” my mother responded at last. “Those things did happen. It was what they used to do a long time ago to the Africans that were forced to come here.” She paused and then, as if she could sense my fears, Mum added, “But they don’t do that anymore. Slavery is against the law now. You have school tomorrow, Nana-Ama. Change your clothes and go to sleep.”

I got up to leave as Fiddler was leading Kunta Kinte away from the auction block, cautiously pulling the chain that was attached to the shackle around the African’s neck.

It didn’t take long for Auntie Comfort to come into the bedroom that I shared with her. I was in bed but still very much awake. My mother’s assurance that the enslavement of Africans was a thing of the past had done little to ease my distress. Auntie Comfort walked over to the small black and white television set in our room and turned it on. She nudged me on the shoulder and told me that I could watch the rest of the show with her. I pointed in the direction of the living room, where I’d last seen my mother.

“You don’t worry,” Auntie Comfort said. I was sure my mother had not consented to this arrangement that Auntie Comfort was proposing. Nevertheless, I sat up and made room for her to sit next to me.

By the time we tuned in again, Fiddler and Kunta Kinte, whose ankle chains had still not been removed, were at the Reynolds Plantation. As a show of his faith and trust in Fiddler, Master Reynolds had assigned him the task of “breaking” the defiant Kunta in to slave life and labor.

Fiddler had taken some water and food to the shed where Kunta was being kept. It was apparent that Fiddler, though firm in his approach, was developing a fondness for his charge. He crouched next to Kunta Kinte and, in addition to the grits and water, Fiddler offered the young slave this bit of advice: “Things start looking better once you stop being African and start being a nigger like the rest of us.”

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. It brought to mind what Jennie’s father, Mr. Potter, had said a couple months earlier about niggers and Africans. Except this time, the words were coming from the mouth of a black person. I had been so convinced that Mr. Potter didn’t know what he was talking about, that he was wrong. So it’s true, I thought, my heart sinking. There is a difference.

When you come from a country where nearly everyone shares the same skin color, you become accustomed to the privilege of being able to think of yourself first and foremost as an individual, a human being. I had once known that kind of freedom in Ghana.

It was fast becoming apparent to me, even at nine years old that this was a privilege America would probably never afford me. No matter how many Fourth of July parades I marched in, no matter how many batons I twirled or safety patrol belts I wore, no matter how hard I tried to fit in; this skin, this blackness would always stand out. In some people’s eyes I would always be “other.” My name, out of some people’s mouths, would always be a filthy word.

Tears were flooding my cheeks. My grandmother pulled me into an embrace and consoled. “Shhh, shhh. I know; I know.” But she didn’t know. She assumed I was crying about the fate of Kunta Kinta; I wasn’t. I was crying about my own fate because I had just discovered that if I stayed in America, sooner or later, I was going to be a nigger, the unsuspecting object of somebody’s blind hatred. All of us would.

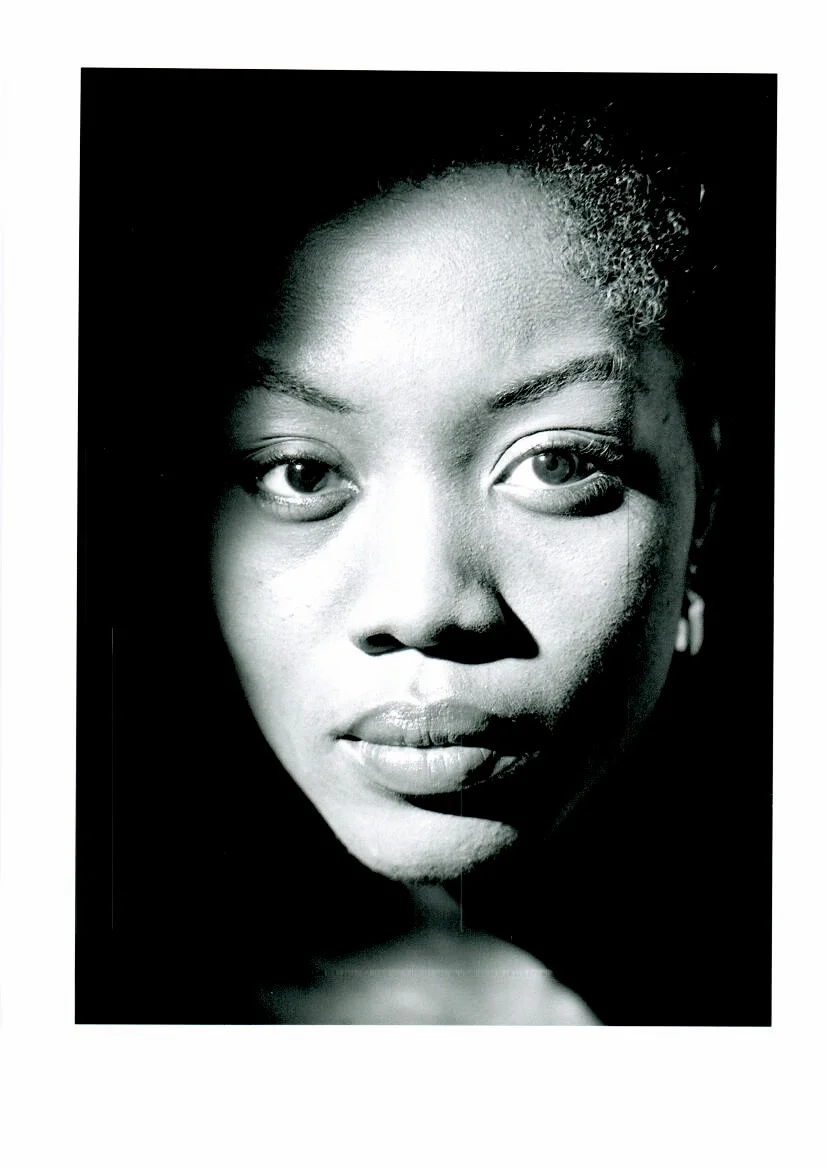

Our Walk to Loggia by Nana-Ama Danquah

Contributor Notes

Meri Nana-Ama Danquah is the author of the critically acclaimed memoir, Willow Weep for Me: A Black Woman’s Journey Through Depression. This chapter is excerpted from her forthcoming memoir, Truer Than the Red, White and Blue: An African Childhood American-Style.