“You see,” he began, releasing the last wisps of smoke around the words. He walked over to where we were. I didn’t look up, but I could feel him standing beside me, wedged into the small space between Jennie’s chair and mine. “It’s true that all niggers are black, but what a lot of people forget is that not all blacks are niggers. Africans are Africans. A completely different breed, straight out of the jungle. You guys aren’t like the common black folks we got here. And I’m sorry to say, a lot of them are niggers, just no good. Nah, if you hear us talking about niggers, don’t think twice because we’re not talking about you.”

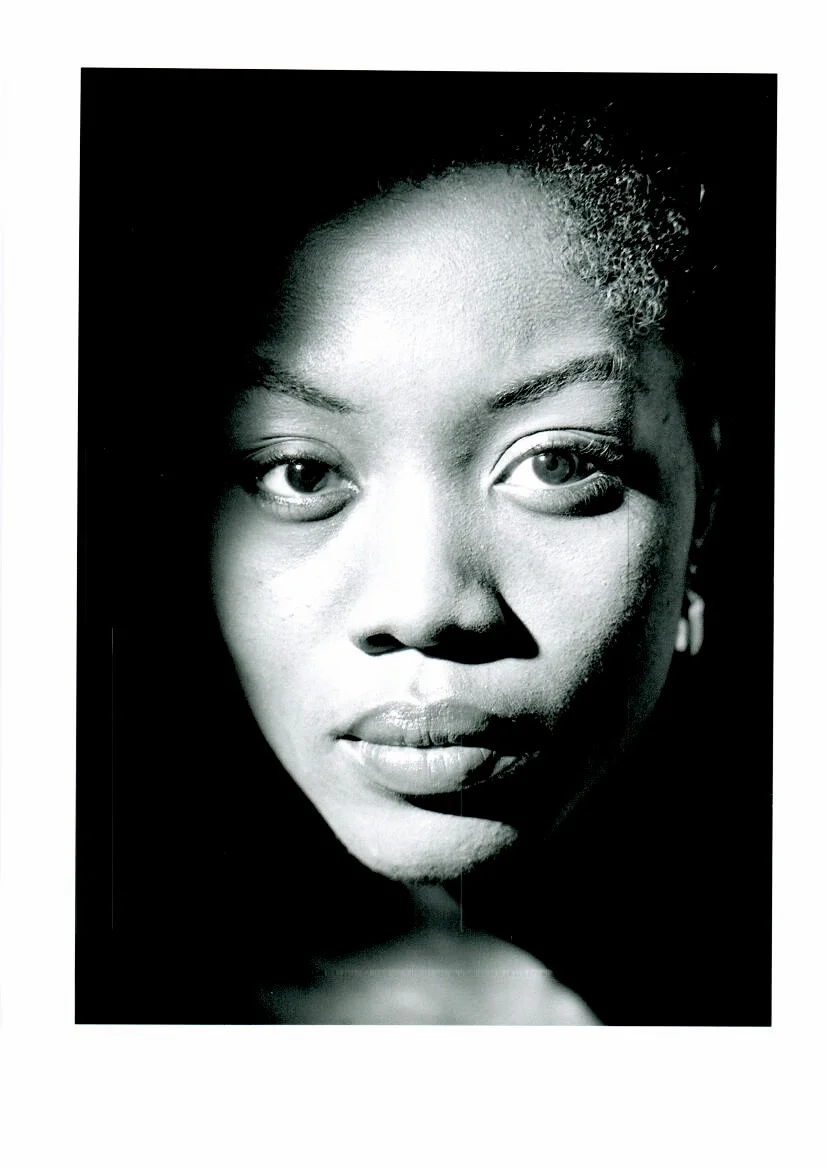

Photo credit: Lyle Ashton Harris

Who Can Afford to Improvise?: Black Music and James Baldwin’s Political Aesthetic by Ed Pavlic (EXCERPT)

Amid the poverty and suffering in and around his Harlem childhood in the 1930s, James Baldwin sensed he’d grown up amidst the performance rhythms in a cultural tradition that kept people from becoming dominated by their circumstances by enabling a nuanced and vital traffic between interior and social worlds. That tradition enacted a level of experience at the border of the secret and the unconscious. For him, it took its most profound and complex form in black music.