Kweli relaunched its Sing the Truth! series in January 2020 as a tribute to Toni Morrison.

During “Art and Social Justice” at the Ambassador Theater, Toni Morrison reminded the audience that artists are “the ones that sing the truth.” The Big Box, Morrison’s first picture book collaboration with her son Slade, sings the truth about “[t]he plight (and resistance) of children living in a wholly commercialized environment that equates “entertainment” with happiness, products with status, “things” with love, and that is terrified of the free (meaning un-commodified, unpurchaseable) imagination of the young.”

Today, in Sing the Truth!, we celebrate activist scholar Debbie Reese (Nambé Pueblo). Debbie Reese publishes the blog “American Indians in Children’s Literature,” (AICL) where educators can find critical analyses of Native content in children’s books. In 2019 she gave the American Library Association’s prestigious May Hill Arbuthnot Lecture and with Jean Mendoza adapted Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s An Indigenous Peoples History of the United States into a version for young people.

Laura Pegram: On your blog, “American Indians in Children’s Literature,” you sing the truth about the good books and the bad. What are some of the specific challenges of singing the truth as an activist scholar?

Debbie Reese: When critics point out the truth, individual and collective responses to those truths are often met with resistance. Rather than consider the truths I offer at AICL, there's a lot of "well, Debbie hates white people" or "Debbie is anti-Black" or "Debbie is too picky" or "Debbie is mean" or "Debbie's criticism doesn't apply because this book is fiction" or "Debbie's concerns with the Native content is important, but the larger issue of X is more important right now, so, I'll use this book anyway." That larger issue can be something like bullying in Touching Spirit Bear. The problems with its Native content is set aside by teachers who think the bullying theme is more important.

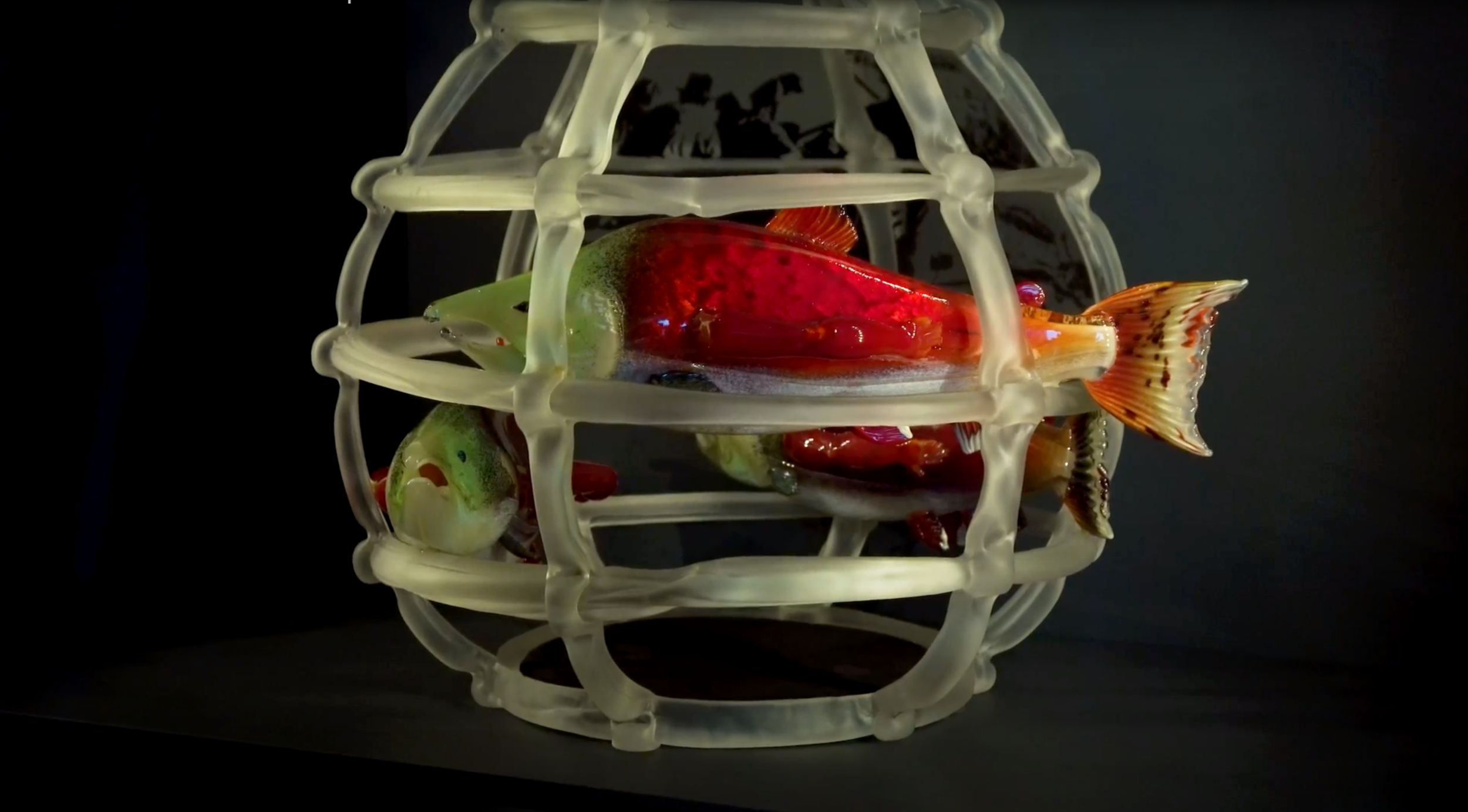

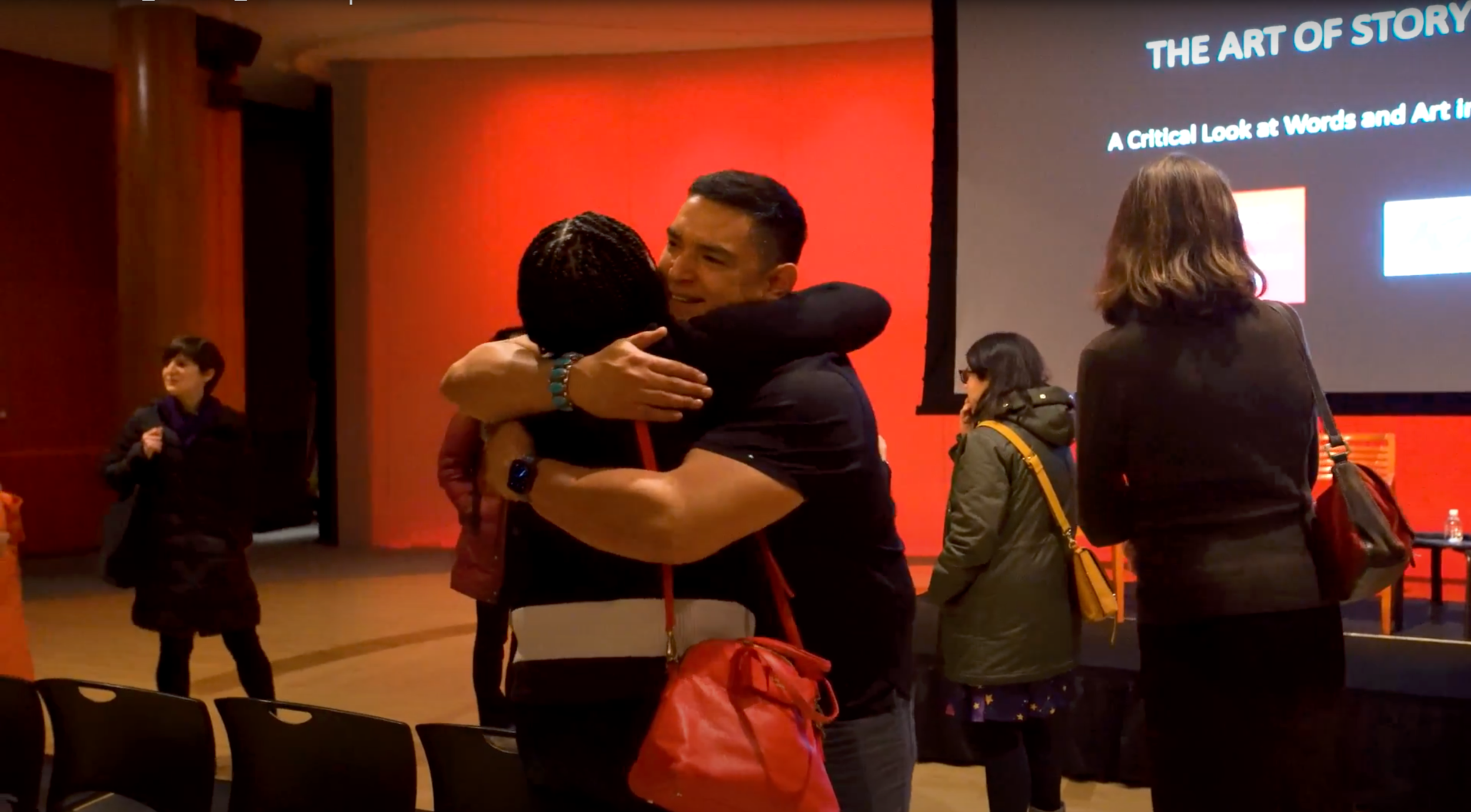

LP: On February 20, Kweli collaborated with the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI-NY) and invited you and Navajo author and filmmaker Brian Young to center stage for The Art of Storytelling, A Critical Look at Words and Art in Children’s Books. At NMAI-NY, you discussed your own identity, your childhood visits to family, your tricycle with the indestructible tires. Then you put yourself in the seat of a fiction writer and told the audience how you would make decisions on the page if you were telling a story. You stressed that you would never write a story if you couldn’t capture the nuance of an experience. Can you please speak about the importance of nuance when creating a work of art for Native children and share a few nuanced lines (or nuanced art) from recent work you reviewed for your blog?

DR: The nuance I am thinking of involves writing about (or illustrating) a place or a people in a way that makes the hearts of the people of that place soar. There's a particular scent when the rain falls at Nambé. There are unique qualities to the way the light comes up as the sun rises over the mountains each morning. Those are intangible, but are things of experience. The way that people in the Upper Village at Nambé do certain things—in food preparation, or song, or story, or ceremony—is not identical to the way the people in the Lower Village at Nambé do those same things. Some of those are tangible. We're able to put them side by side and see the difference. We might engage in joyful banter about why this or that item is "better" than the one next to it. Oh! I think of Kevin Maillard's picture book about fry bread as I write about tangible items! His writings about the many ways of making fry bread are perfect!

Getting back to nuance of place: I'd know it when I read it. If I was writing fiction, my hope would be that I'd be able to capture those nuances. My mother grew up at Ohkay Owingeh, which is about 20 miles from Nambé. We went there all the time to visit her dad, sister, and brothers (my grandfather, aunt, and uncles). Of course, we would play with our cousins. What I'm getting at is this: I was there a lot as a kid, but I wouldn't write a story set there or create a main character from there because I don't know those intangible characteristics of daily life there. Today, I could go there and stay awhile, but I don't think I would be able to make that story sing. My cousins there would pull me aside and say "DEB!" If I developed a character from Nambé who goes to Ohkay, I would obviously be writing about Ohkay from a Nambé point of view.

Stepping from that tribally specific discussion to one that is broader, but still Indigenous, there are ways to communicate nuance. In Cynthia Leitich Smith's picture Jingle Dancer there's a page that made me stop immediately. On that page, there's a trunk over against a wall. To most readers, it is just a trunk. To a Native kid, that trunk has meaning. Many of us store our regalia in trunks. When the illustrations were being done for that book, Cynthia and the illustrators were in touch with each other. It made a huge difference. Similar conversations took place between Kevin Maillard and Juana Martinez-Neal. As I pored over the pages of Fry Bread, I saw things like that trunk in Jingle Dancer. I understand that Carole Lindstrom and Michaela Goade were in similar conversations when they worked on We Are Water Protectors. I look forward to seeing how Michaela captured unique aspects of Carole's identity on those pages.

LP: Let’s look at the 2018 Diversity in Children’s Books infographic you shared at NMAI-NY. How long do you think it will take before those shards of glass at the feet of Native children are replaced by a full mirror?

DR: That's a question that evokes distress. People have to know who we are—for real. Right now, those shards of glass are there because the "knowledge" people have about us isn't knowledge at all. It is stereotypes. When I look closely at the books that make up the raw data on the infographic, I see that major publishers are the ones doing the problematic content. They are affirming stereotypes and stereotypical thinking! The consequence is that when Native writers tell their stories, non-Native readers can't see their characters as Native because they don't look like the stereotypical image they hold in their heads. I am hopeful, though! New developments, like the Heartdrum imprint that Cynthia Leitich Smith is bringing forth, give me hope.

LP: Would you care to share any articles for teachers and educators that they can fall back on as they prepare reading lists for their students?

DR: "Critical Indigenous Literacies: Selecting and Using Children's Books about Indigenous Peoples" was published in Language Arts in 2018. That journal is published by the National Council of Teachers of English. It is online, here:

https://secure.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Journals/LA/0956-jul2018/LA0956Jul18Language.pdf

"12 Picture Books that Showcase Native Voices" is in School Library Journal. It is online, too.

https://www.slj.com/?detailStory=1809-Native-Voices-American-Heritage

Kara Stewart (Sappony) and I wrote "Native Stories: Books for tweens and teens by and about Indigenous Peoples" for School Library Journal:

https://www.slj.com/?detailStory=great-books-native-stories-indigenous-peoples-tweens-teens

LP: In your Teaching Tolerance interview, you talked about the importance of using a combination of texts when teaching about Indigenous people. Can you elaborate on that a little bit?

DR: When people think about Native peoples, they seem to default to traditional stories (mislabeled as folktales) and works of historical fiction. The nature of both genres put us in a long-ago and far-away context. Instead of teaching young children about Native people of the present, the defaults are centered on Columbus and Thanksgiving--and neither are taught critically! So--I think teachers have to learn about Indigenous peoples of the present day and start their instruction in the present rather than the past.

LP: At NMAI-NY we discussed the hashtag #OwnVoices. Can you talk about the importance of moving towards the use of #TriballySpecific hashtags?

DR: That's related to the nuance I talked about above but I can say more, here.

There are teachings within any Native Nation that are there to protect that nation from the harms we've experienced in the past. There are protocols of what can and cannot be shared with others, and there are protocols for what visitors can and cannot do. On many reservations, there are signs that say "no photos, sketching, or audio or video recording." If a visitor does it anyway, someone who has authority to do so will take your materials from you. These protocols are there to protect ceremony's from being misrepresented or exploited for personal gain. This is especially the case when a writer misrepresents or uses content that is off-limits to outsiders. That sort of use is harmful to the well-being of individuals of the specific nation or the nation itself. If I violated the protocols, my community at Nambé would hold me accountable.

Though Native peoples have similarities across our many nations, there is very real risk that a Native writer who writes about another Nation will violate those protocols. The #OwnVoices hashtag isn't specific enough. It's meant to tell readers that the writer and the main character share an identity that has been marginalized by society, but if the writer is pueblo and creating a main character that is Navajo, that is not #OwnVoices. Assuming that any Native person can write about any other Nation obscures the facts that we're unique. It treads too close to the idea that we're a monolith. My growing awareness of the shortcomings of the hashtag is why I'm moving to tribally specific information when I'm on Twitter. I've been very mindful of the importance of being tribally specific, for decades, and worry that I've inadvertently used a hashtag that is too broad. So, when I'm using social media to talk about Cherokee writer Andrea L. Rogers and her book about the Trail of Tears, I'll use #CherokeeVoice rather than #OwnVoices.

LP: Thank you for Singing The Truth! with us, Debbie. It takes a lot of courage to speak truth to power. We celebrate you and the critically important work you do as an activist scholar.